There is a scene in S. Leo Chiang’s Oscar-nominated documentary short Island in Between where two men discuss a fierce battle. One mentions a memorial for fallen soldiers on the opposite side of the strait that separates them from China. The other seems surprised something like that would exist.

“Duh! They fought us. Of course they have one, too,” the first responds. ” Their civilians fought and died, too, like our side.”

Their conversation – which plays out against footage of disused military facilities on the Taiwan-governed islands of Kinmen – is one of several vignettes in Chiang’s poetically paced film where a prosaic compassion pervades, exposing the nuanced reality behind deeply rooted rhetoric.

Islands in between

In Island in Between – released on The New York Times’ Op-Doc channel last September, a few months ahead of Taiwan’s general election – Kinmen is both a literal and figurative embodiment of that nuanced reality.

Kinmen, a group of 12 islands less than five kilometres from the Chinese city of Xiamen at their closest point and around 200 kilometres from Taiwan, was the scene of major hostilities during the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and beyond, when the Kuomintang nationalists fought the Communist Party for their control, and won.

Even now, as analysts debate the likelihood of Beijing invading Taiwan in an effort to bring what China considers a renegade province under its governance – as has frequently been the case in recent months – they often mention Kinmen in the same breath.

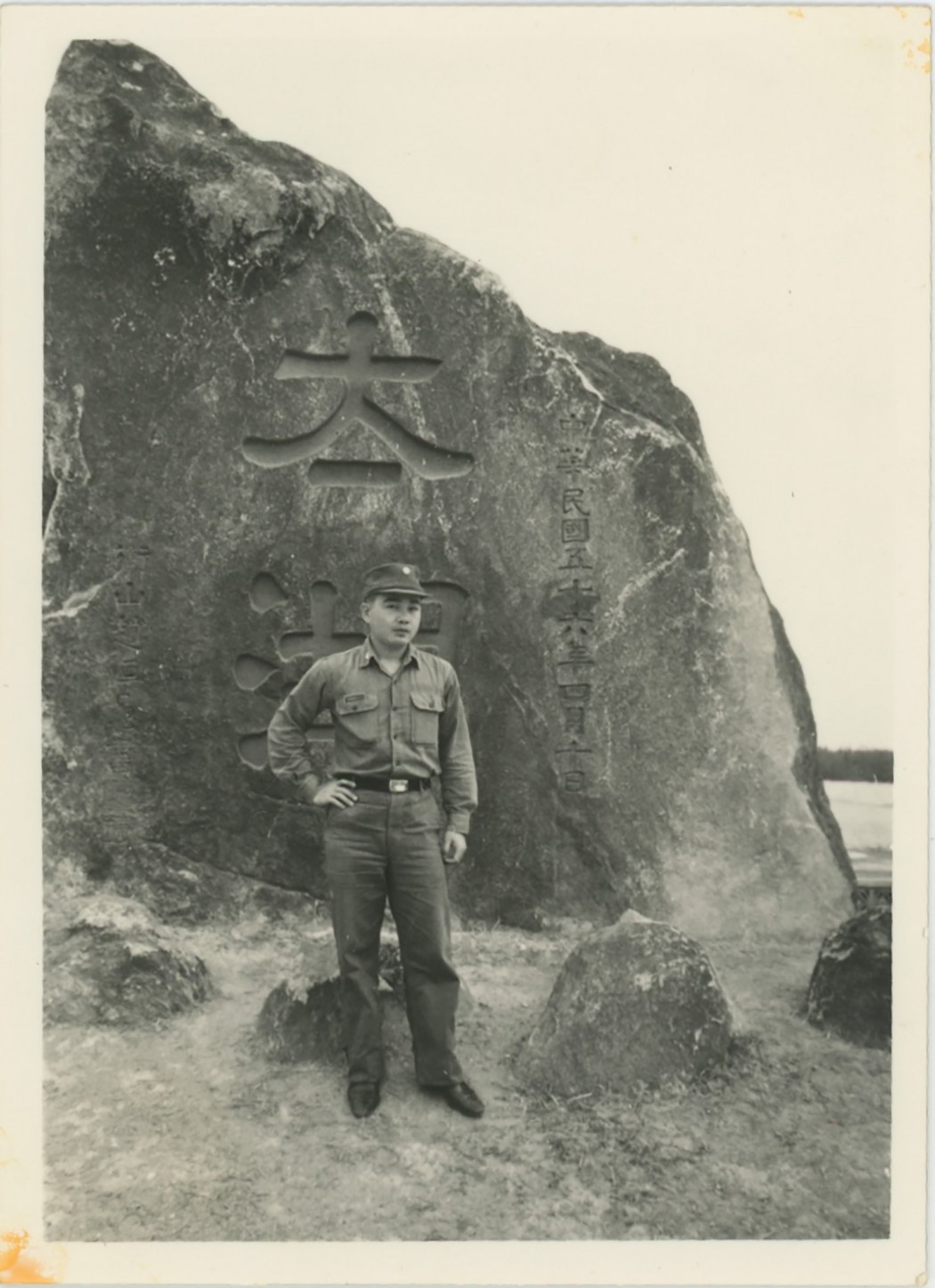

But for Chiang, Kinmen is more than a point on a historical map or the site of further, future conflict – it is where his father did military service in the 1960s.

It was not until 2020 that Chiang explored the islands, though. The Covid-19 pandemic had shut several borders, forcing him to accept Taiwan as his home base after spending most of his adult life in the US.

And so, with international travel off the agenda, Chiang and his parents decided to travel to Kinmen “because my father had been there, because I’ve always been kind of curious about it,” he told HKFP by video call from Taipei last Monday.

“The film came after,” he added.

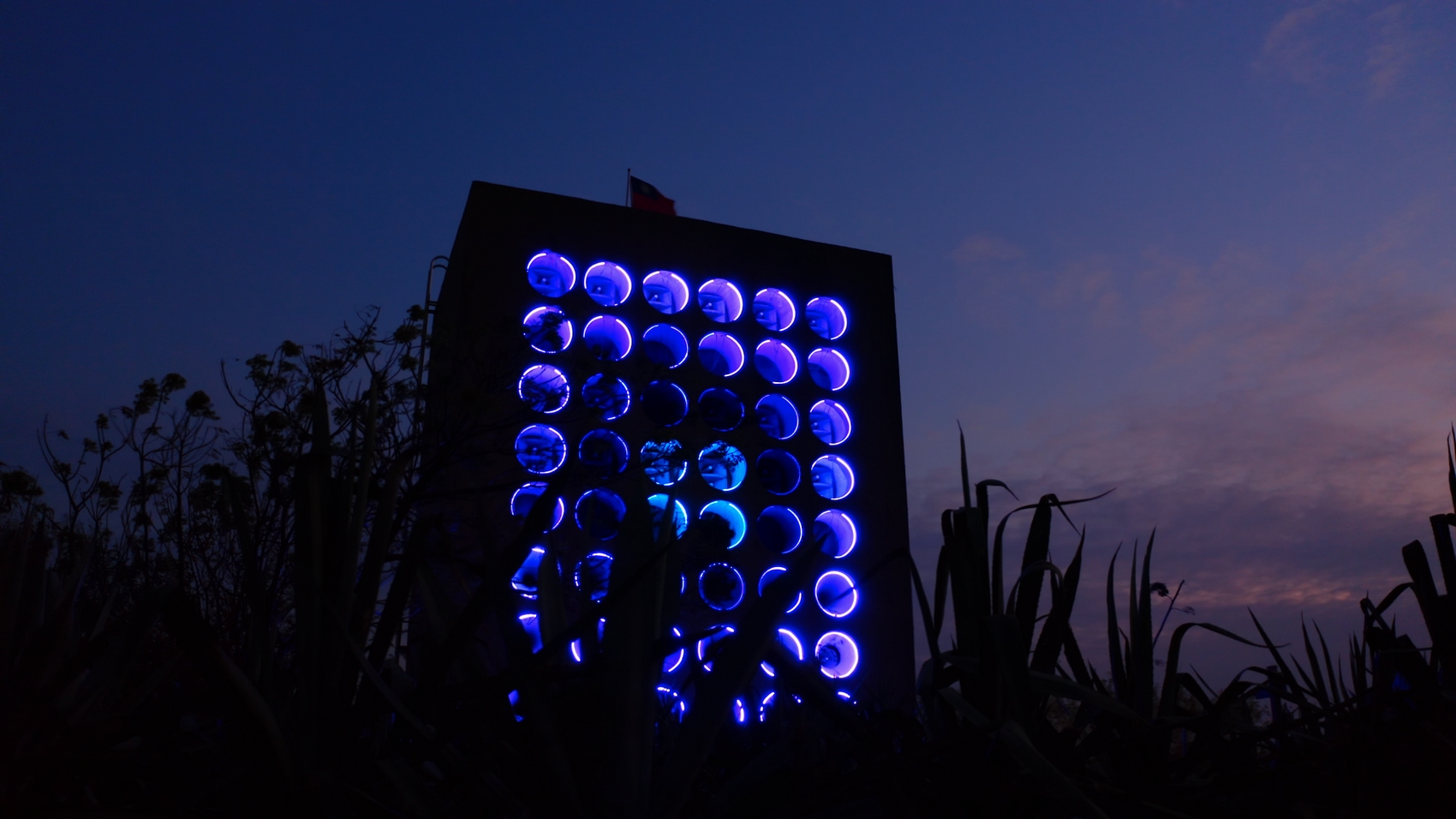

What he found was a place that felt both separate from and part of Taiwan. Somewhere that does not shrink from its bloody history, but wraps it in nostalgia to sell to tourists, where hits by the late Taiwanese pop star Teresa Teng blare from a brutalist concrete speaker and portraits of Mao Zedong hang alongside those of outgoing Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen.

See also: Decades after the end of White Terror, Taiwan still struggles to come to terms with its painful past

“If anything, it does in some ways feel like Taiwan… maybe 20 years ago,” Chiang says. “Which also makes a lot of sense because of the timeline… because they stayed under the more restrictive system longer than Taiwan island.”

While Taiwan’s repressive martial law period under Kuomintang rule officially ended in 1987, the people of Kinmen did not emerge from martial law until 1992.

“As the younger generation comes up, the identity’s changing,” Chiang says.

‘Enemy territory’

Perhaps surprisingly, prior to the pandemic, Kinmen had placed its bets not on war with China, but on arrivals from across the water. Connected to Fujian province by a 30-minute ferry ride, in 2019, some 40 per cent of Kinmen’s 2.5 million visitors were mainland Chinese.

“If you go to Kinmen now, you see this infrastructure that was clearly built during the boom times,” Chiang says, listing shopping malls, duty free stores and huge hotels. “It’s now basically deserted because this big flock of mainland tourists has not come back, or has not been able to come back.”

Shuttered during Covid, the ferry services have now resumed. But not for everyone.

“The Kinmeners who have investments, relatives in Xiamen are still allowed to go. The other side aren’t allowed, or not as freely,” Chiang says.

Without tourists from China, Chiang was unable to pursue an angle he had hoped to explore: “how the mainland Chinese tourists see this place.”

“You know, it’s like you go and visit the quote-unquote enemy territory, and you see how the same thing you grew up learning about is not that scary,” Chiang says. “I’ve always been very fascinated by that dynamic.”

It is one he is familiar with. Chiang grew up under martial law, believing that the Kuomintang would conquer China, and singing songs with lyrics such as, “Destroy Mao and kill traitors of the Chinese race!”

Then, aged 15, he moved to the US, and learned a whole new version of events, which made “that idea that this population of 20-something million can overturn [Communist Party rule]… just seem absurd.”

“The history I learned about Taiwan [before leaving], it’s very different from the history that I learned after I left Taiwan,” Chiang says. “You know what they say about ‘history is with the victors,’ it’s very much that way,” he continues, adding that was exemplified by “how huge a hole” there was between “what I knew before versus actually what is the reality.”

Chiang discusses a similar dissociation between perceived knowledge and reality in Island in Between – when he began working in China.

“The China I saw was not the sad and scary Communist wasteland that I learned about in school,” Chiang tells the viewer through a voice-over. “It was an exhilarating place, bursting with colours and possibilities.” On screen, a chorus of voices sing the same Teresa Teng song that blares every night out of Kinmen’s Cold War-era speaker wall.

For anyone who has not been to China, it is a humanising sequence.

“That’s very much the intention,” Chiang tells HKFP. “Do I agree with a lot of the policies of the [Chinese] government? No, absolutely not, but that’s not what the people are like. Sure there’s a portion, and maybe a big portion, that does support the government policy but there’s also a diversity of opinion that is not being heard outside,” he continues.

“People outside of the region do not understand the nuances of that and I do hope that’s what’s coming across in my film.”

‘Self-censorship is the worst kind of censorship’

When Chiang started worked in China, in 2005, he did so under his US passport as Beijing does not recognise Taiwan sovereignty, instead issuing Taiwan Compatriot Permits that essentially strip Taiwanese visitors of their citizenship.

Chiang explores this complexity of identity in Island in Between and in conversation with HKFP. “I would really prefer to be described as somebody that has two nationalities,” Chiang says. “The fact is I am both [Taiwanese and American] and I am also in-between.”

This in-between, though, is not a physical space, like Kinmen caught between Taiwan and China, or even Taiwan caught between China and the US.

“This is all about the, not even just about the in-betweenness of identity in terms of sort of feeling trapped by the pressures, but it’s also the grey areas between the extremes that we always hear about,” Chiang says.

“Either ‘the sky is falling, [China is] coming tomorrow,’ versus a lot of the people [in Taiwan], or in Kinmen, saying ‘it’ll never happen, it’s pure hysteria. Neither of which is true… no one really knows when and how and if – because the Chinese government, their decision making process is so opaque, there’s no way to predict it. Everything is speculation.”

Amid such conjecture, Chiang continued working in mainland China until just before the pandemic. “Most recently, I made a feature-length documentary… that was finished and released in 2019.”

It has not yet been shown in mainland China.

“It was about father-son artists, it was about ageing, it was about Alzheimer’s, it was about families, it’s about memory,” he says.

“I didn’t consider it to be a sensitive film… But of course if you talk about artists of a certain generation, you would touch on the Cultural Revolution… so the very mere mention of it put us in a censorship dilemma,” Chiang recalls.

“It’s one of those deals where they say, ‘well, we won’t accept this,’ and we would say ‘well, what would you accept?’ and they say, ‘we’re not going to tell you, you’re have to go figure it out.’ And of course we all know that self-censorship is the worst kind of censorship.”

Discussion turns to the increased pressures Hong Kong filmmakers face trying to get their work past the city’s censorship authorities, as well as a recent clampdown on the performing arts sector. Within the space of a few weeks, funding, plays and venues have been pulled.

“It’s just sad,” Chiang says. “I love Hong Kong.”

He has not visited since Beijing imposed its national security law on the city in 2020, criminalising secession, collusion with foreign forces, subversion and terrorism.

“I’ve actually been kind of avoiding it,” he says. “Not necessarily because I think something is going to happen to me… I just, I feel like it’s some little way of protesting,” he adds.

“A lot of the Taiwanese folks really… look to Hong Kong and the choices that, well, maybe not choices… things that happened to Hong Kong and what that means potentially for Taiwan if that’s the path that it goes down,” Chiang says. “Hong Kong is a cautionary tale.”

Chiang mentions in Island in Between that he is unsure when he might next visit mainland China.

“I actually haven’t really thought through it,” he tells HKFP, saying he had become more “visible” because of the Oscar nomination, which was announced on January 23.

“Interestingly enough, I have been producing for a couple of Chinese filmmakers and one film is being released where they were advised that I don’t put my name on it. So, who knows? I don’t know.”

For now, though, Chiang is forgoing the Lunar New Year break, flying from Taiwan to the US on Saturday for screenings and publicity in the run up to the 96th Academy Awards on March 11.

Of the awards ceremony, he says he is “very excited.” Anyone who doubts that should see his reaction to securing the nomination, recognition that puts him very much among – and not between – other celebrated filmmakers.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

Original reporting on HKFP is backed by our monthly contributors.

Almost 1,000 HKFP Patrons made this coverage possible. Each contributes an average of HK$200/month to support our award-winning original reporting, keeping the city’s only independent English-language outlet free-to-access for all. Three reasons to join us:

- 🔎 Transparent & efficient: As a non-profit, we are externally audited each year, publishing our income/outgoings annually, as the city’s most transparent news outlet.

- 🔒 Accurate & accountable: Our reporting is governed by a strict Ethics Code. We are 100% independent, and not answerable to any tycoon, mainland owners or shareholders. Check out our latest Annual Report, and help support press freedom.

- 💰 It’s fast, secure & easy: We accept most payment methods – cancel anytime, and receive a free tote bag and pen if you contribute HK$150/month or more.

MORE Original Reporting

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.