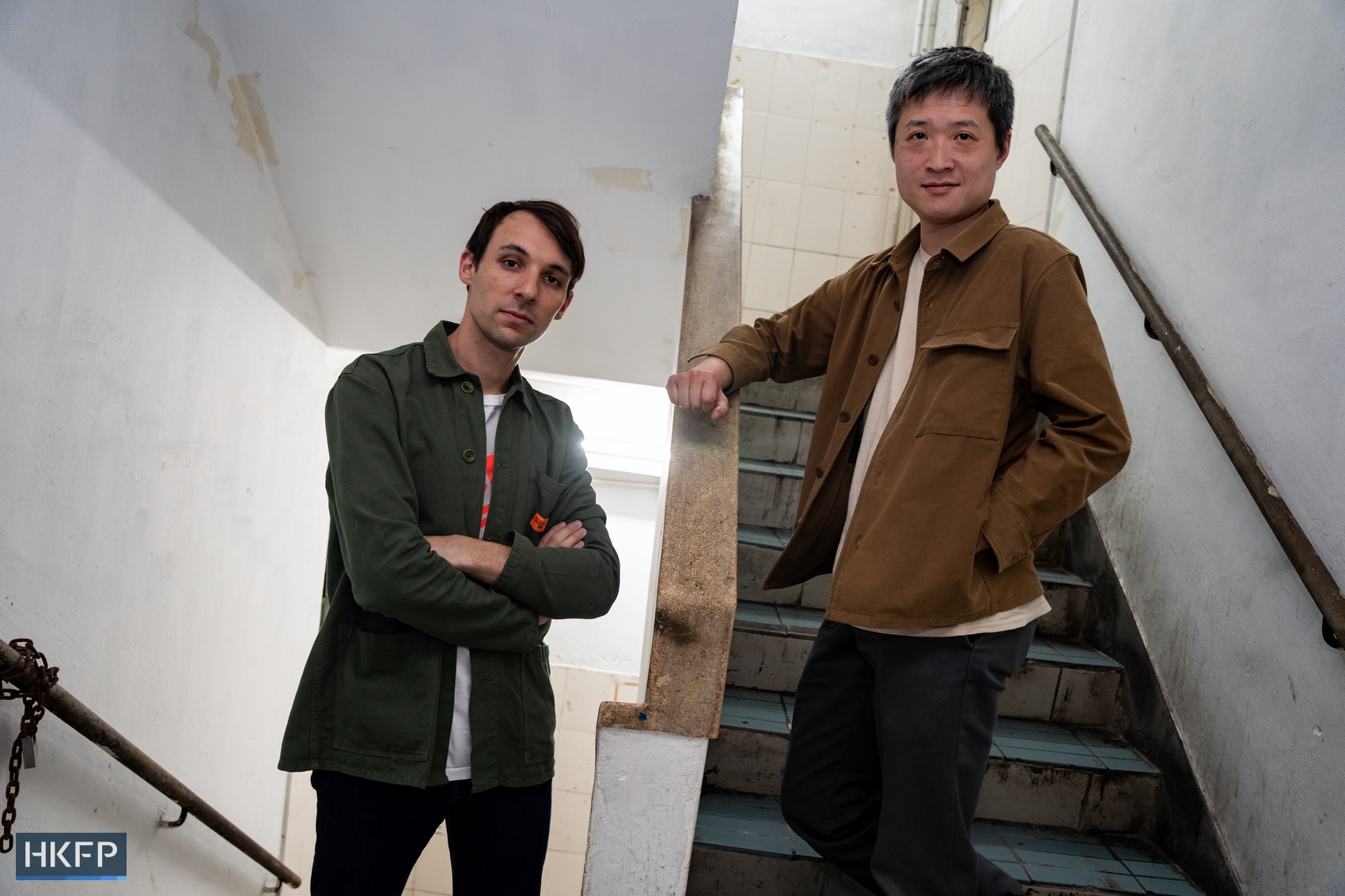

From a record store in Suzhou, to a former Taoist temple in Zhejiang province, to a dive bar called Wuhan Prison in China’s punk capital, Beijing-based post-punk duo Gong Gong Gong 工工工 have spent the last month working their way southwards across the country before arriving in Hong Kong ahead of their Clockenflap debut on Friday.

The Chinese capital, though, is more of an adoptive home for the pair. Guitarist Tom Ng sings in Cantonese, punctuating the chug-chug-chug of distorted blues-infused post-punk with a guttural drawl that oscillates between insouciant and assertive — an unmistakeable hallmark of his Hong Kong roots. Joshua Frank, born in Montreal and brought up in Beijing, matches bass melodies in lockstep.

Boundaries, for the band, are malleable. Their debut album Phantom Rhythm 幽靈節奏, named after instrumental patterns that emulate percussive elements without actual drums, was recorded in Brooklyn. The upcoming release Mongkok Duel 旺角龍虎鬥 was recorded as a split album with Taiwanese psychedelic two-piece Mong Tong in Hong Kong.

This bricolage of language and localities, expressed through nothing more – and nothing less – than a guitar and a bass, has garnered Gong Gong Gong a global following as particular as the band’s sound. “I mean, we are all of these things, but we’re actually, not really any of those things,” Josh said, referring to Gong Gong Gong’s many geographical labels as Canadian, Hong Kong, and Beijing bands. “Playing a show in Hong Kong or in mainland China or in the States or in Europe isn’t that much different for us.”

Despite widespread acclaim and international reach, smaller and more intimate settings are where the band thrives. “We’ve played big shows, like when we played in the US we played thousand-person venues, full house, no problem,” Tom told HKFP by video call on Wednesday while the pair waited for their Hong Kong flight in Beijing.

“But as performers, we would think that playing in a small venue is just more interesting for us. Playing on a big stage is kind of like playing to yourself, a little bit.”

Behind Gong Gong Gong’s approach to curating and organising gigs is an ethic typical of the independent music scene. “I mean, we like to do things ourselves,” Josh said. “There’s a reason why we haven’t done tours that are managed by a big promoter, because we’re happy with how we do it, and we can make the time to figure out the way that we like things to be done.”

The pair had just finished practicing for their Friday set when HKFP visited at President Piano Co. in Mong Kok, a legendary rehearsal studio established in 1978. “Maybe I’ll pretend to be physically bigger at Clockenflap,” Tom laughed. “It’s exactly what you’d do if you see a bear – you pretend to be bigger and scarier,” added Josh.

Homecoming

During the pandemic, the band was forced to unplug. But after Hong Kong reopened its borders and dropped its stringent Covid curbs early this year, Gong Gong Gong played a set at Soho House, riding on something of a pandemic-induced boom in the local indie scene. A mosh pit opened up to the rhythmic plodding of guitars at the Sheung Wan club, as if fans were releasing pent-up frustrations with every chord. “It was probably the most intense reaction we’ve had to our music, ever,” Josh said.

The local scene was left to its own devices during the pandemic. Without festival headliners to look towards, it seemed fitting, if not ironic, that Hong Kong would have to look within in the wake of the 2019 anti-extradition protests. And somehow it was able to thrive, if only for a few months.

The band’s relationship with city goes further back. Before Gong Gong Gong formed a little less than a decade ago, there was the Hong Kong indie scene of the 2000s — a fledgling counterculture hidden away in industrial buildings due to bureaucratic property rules and sky-high rents. “I didn’t move to Beijing until 10 years ago, so I was playing in other bands in Hong Kong. But the local audience didn’t really care about the local music scene that much,” Tom recalled. “Now it’s become such a big thing.”

Back in the mid-noughts, Tom played in another band, The Offset: Spectacles, sharing stages at gallery spaces such as Para Site with Nicole Au, who makes up one half of My Little Airport, the indie-pop duo that has become a Hong Kong pop-culture mainstay over the course of its two-decade career.

“There’s this new band I’m really curious about: Catscare,” Tom mused. He was referring to a newly formed group fronted by Nicole, with Nic of now-inactive post-hardcore legends The Lovesong on bass, and Paul McLean of Nan Yang Pai Dui, known otherwise as NYPD, on drums. “They were asking if we wanted to play a secret show in Hong Kong, but it didn’t work out, so maybe next time,” he added.

Language and borders

Ng named NYPD, which will return to the Clockenflap stage on Saturday following a tour spanning China, Taiwan, and Korea this summer, as well as noise virtuosos David Boring and experimental spoken-word duo XSGACHA 小本生燈 among Gong Gong Gong’s pantheon of Hong Kong acts.

As evident in NYPD’s brash, unadorned lyricism as well as Gong Gong Gong’s Wei Wei Wei 喂喂喂, in which Ng hammers the Cantonese colloquialism for “hey” over a riff that wouldn’t sound out of place in a spaghetti Western, language is the linchpin in the local underground scene.

While sonic elements are allowed to shine, the linguistic mystique of Cantonese in mainland China begins to wane the further south the band goes, replaced with more semantic familiarity.

“Once we get to Guangdong, you start having a lot more people who speak Cantonese – the reaction is really different, especially in Guangzhou,” said Tom. “You never really have 200 people singing along with us, so it was quite an experience.”

Hong Kong’s scene is smaller and less influential than overseas, made up of bands that struggle – or perhaps don’t bother – to take off internationally. And for some, the prospect of a northbound tour is a complex issue.

But in a way that’s reminiscent of Gong Gong Gong’s touring experience, other Hong Kong acts may not see performing in mainland China as such a different experience from touring in Taiwan or Japan. It’s a process of coming together with the punks, misfits, and outcasts in the crevices of each locale.

The challenge lies in navigating an entirely different system, Josh said. “There’s obviously some bureaucracy, and if you don’t know how things work, you need someone to show you the way a little bit. I mean, we don’t have Chinese passports, we have to stay in hotels that so-called ‘foreigners’ are allowed to be in, and deal with that kind of stuff. But at the same time, it’s actually really easy to tour in China.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

Original reporting on HKFP is backed by our monthly contributors.

Almost 1,000 HKFP Patrons made this coverage possible. Each contributes an average of HK$200/month to support our award-winning original reporting, keeping the city’s only independent English-language outlet free-to-access for all. Three reasons to join us:

- 🔎 Transparent & efficient: As a non-profit, we are externally audited each year, publishing our income/outgoings annually, as the city’s most transparent news outlet.

- 🔒 Accurate & accountable: Our reporting is governed by a strict Ethics Code. We are 100% independent, and not answerable to any tycoon, mainland owners or shareholders. Check out our latest Annual Report, and help support press freedom.

- 💰 It’s fast, secure & easy: We accept most payment methods – cancel anytime, and receive a free tote bag and pen if you contribute HK$150/month or more.

MORE Original Reporting

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.