When Astrid Andersson tells people what she does for a living, she is often met with incredulity. “People don’t believe me when I say I’m a cockatoo researcher,” Andersson said on the latest episode of HKFP’s podcast Yum Cha. “But it’s true.”

The postdoctoral researcher at the University of Hong Kong has dedicated her scientific career to investigating the white birds with a bright yellow crest and unforgettable squawk that can be seen – and heard – in many of the parks on Hong Kong Island as the sun rises and sets.

Native to East Timor and a handful of Indonesian islands, with wild landscapes of rugged hills interrupted by thorny thickets of green, yellow-crested cockatoos do not really belong in Hong Kong.

Chankalun – A Bright Future for Hong Kong's Neon Heritage – HKFP Yum Cha

- Chankalun – A Bright Future for Hong Kong's Neon Heritage

- Carol Liang – Happy Hong Kong?

- Astrid Andersson – Wildlife Trade and Alien Invaders

- Xyza Cruz Bacani – Migrant Domestic Workers and the Children Left Behind

- Cynthia Cheng and Maxime Vanhollebeke – An Invisible Web of Workers

- Vaudine England – A City Between East and West

- Regina Ip – Matters of Security

- Emily Lau – Fighting Two Tigers

Apple | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | Overcast | Amazon Music | Pandora | RSS

“It’s a really unusual situation,” Andersson told HKFP, sitting on a bench in the middle of Hong Kong Park, an 80,000-square-metre green enclave in the heart of the city. “We’re here in, like, the most urban and developed and cosmopolitan part of Hong Kong really – [it’s] Admiralty, we’ve got major banks, it’s the CBD, basically – and here is the hot spot, the real home base, for cockatoos in Hong Kong. It’s bizarre.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature puts the remaining global population of Cacatua sulphurea somewhere between 1,200 and 2,000, making the species critically endangered. About 200 of those live in Hong Kong, according to Andersson’s estimates.

How they came to nest in the cotton trees on Hong Kong Island is the stuff of urban folklore. and something that Andersson tried to get to the bottom of during her PhD.

“The most popular theory is that the governor of Hong Kong, during the Japanese invasion in World War Two, he had a bunch of these cockatoos as pets and when the Japanese were advancing, he released them, and… that was the founder population,” Andersson said.

“But I do think that, even if that’s true, this population is most likely supplemented by continual escapees or released individuals, because when we do we do an annual cockatoo count… I always see a few individuals that I notice are of a slightly different subspecies or… a different species altogether, mixed in.”

Regardless of how these birds became one of the city’s invasive species, how yellow-crested cockatoos arrived in Hong Kong is unambiguous: via the pet trade.

“They actually are a very popular cage bird pet,” Andersson said. “Especially in the 1980s and early 1990s, yellow crested cockatoos… were very popular. There were over 70,000 of them exported from Indonesia at that time… and it’s around then that they started showing up in Hong Kong, as well, in large numbers.”

That industry has been central to their decline.

“In Indonesia, unfortunately, the major pressure has been trapping for the pet trade. So, during the 80s and 90s when it was still perfectly legal to do so, they were trapped rates that were just completely unsustainable, and then, actually, that has continued,” Andersson said.

Internationally, trade in wild-caught yellow-crested cockatoos was banned in 2002, but the sale of captive-bred birds remains legal. And while rigorous protections are in place to protect the native population on Indonesia’s Komodo Island, the Asian Species Action Partnership has noted that “trapping for the pet trade continues with declines noted in almost all other populations.”

Andersson recalled an incident in 2015, when a man was arrested after being found by Indonesian authorities with more than 20 birds stuffed into plastic bottles. “They were illegally trapped,” she said, adding that while “that’s the major threat they face” the birds were also contending with human-led habitat loss and the impacts of the climate crisis.

Another issue, was identifying captive-bred birds from ones that had been illegally captured from the wild. There were methods in place, Andersson said, but during surveys of Hong Kong’s Yuen Po Street Bird Market conducted during her PhD, she found that they did not appear to be routinely applied.

“You’re supposed to see that they have a band on their leg with an ID number,” she said. “But when I was doing the survey, I noticed a few birds didn’t have a band, or they had a band that… you could remove, or it didn’t have a number on. There didn’t seem to be a really consistent standard for these identification and traceability means,” she continued.

“The issue arises when you can’t really tell, say, [whether] a cockatoo has been smuggled from Indonesia in a plastic bottle, and then put in the bird market.”

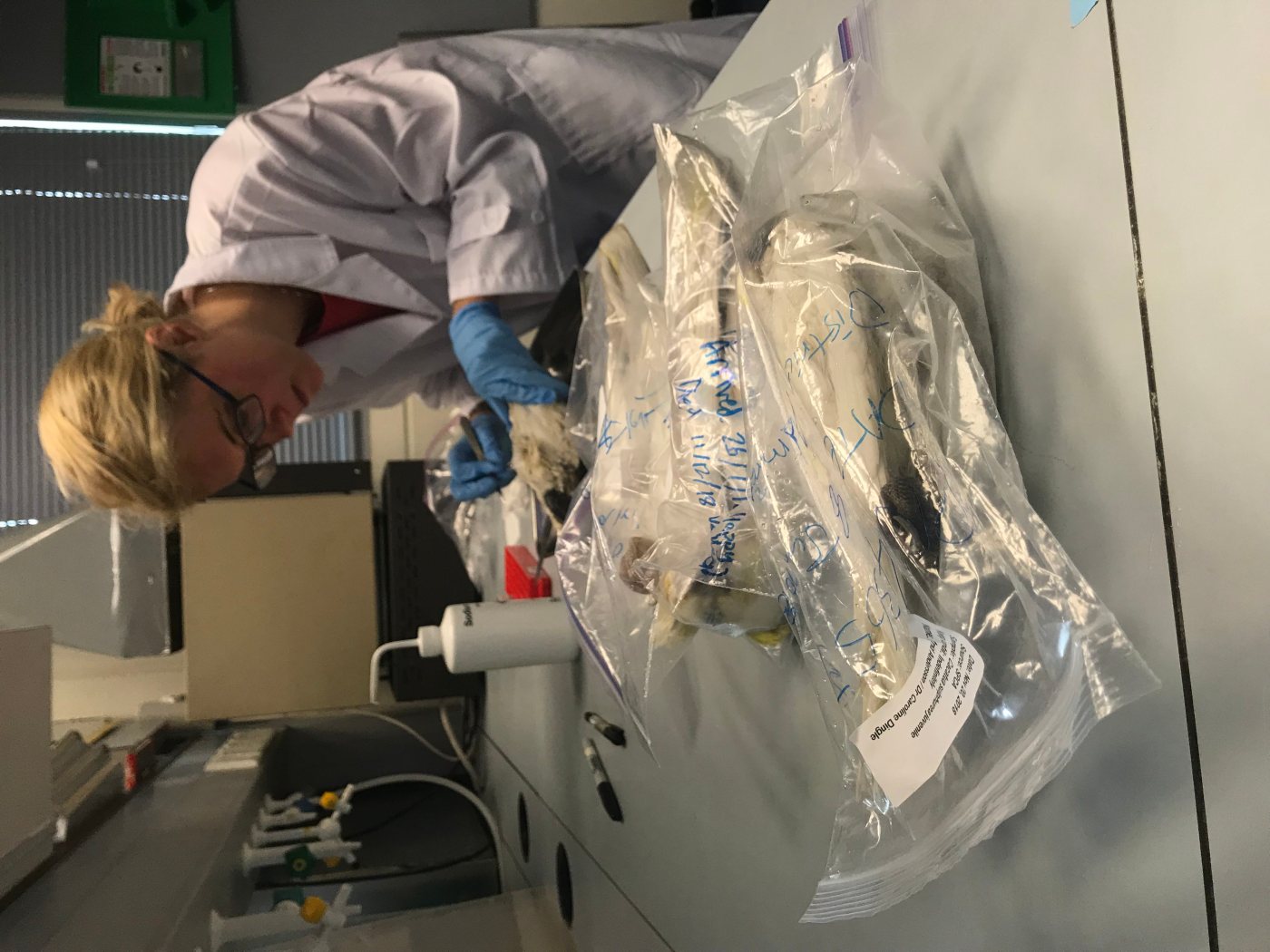

After completing her PhD in 2021, Andersson turned her focus on the genetic makeup of Hong Kong’s cockatoos, “trying to figure out: are they inbred, are they hybrids or are they… pure subspecies of yellow-crested cockatoos? Are they from a certain island in Indonesia or another one… that sort of thing.”

Her findings could be important not only to help understand the city’s population, but perhaps for the conservation of yellow-crested cockatoos in their native habitats.

“If there was genetic rescue needed in Indonesia, and it was assessed to be safe, and all of the proper procedures that you have to do when you reintroduce birds were followed… it could turn out that Hong Kong has actually provided a reservoir, a genetic reservoir for this critically endangered species,” she said.

Gesturing to the skyscrapers that surround Hong Kong Park, Andersson added: “I don’t know that the bankers working in these towers here in Hong Kong know that when they look out the window while they’re on their conference call and they see these birds flying past, it’s actually a really rare species.”

HKFP Yum Cha

New episodes of HKFP Yum Cha are published on Saturdays. The first season features a diverse range of voices, from artists to scientists, who share their perspective on Hong Kong as it is today through the lens of their industry.

Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

Original reporting on HKFP is backed by our monthly contributors.

Almost 1,000 HKFP Patrons made this coverage possible. Each contributes an average of HK$200/month to support our award-winning original reporting, keeping the city’s only independent English-language outlet free-to-access for all. Three reasons to join us:

- 🔎 Transparent & efficient: As a non-profit, we are externally audited each year, publishing our income/outgoings annually, as the city’s most transparent news outlet.

- 🔒 Accurate & accountable: Our reporting is governed by a strict Ethics Code. We are 100% independent, and not answerable to any tycoon, mainland owners or shareholders. Check out our latest Annual Report, and help support press freedom.

- 💰 It’s fast, secure & easy: We accept most payment methods – cancel anytime, and receive a free tote bag and pen if you contribute HK$150/month or more.

MORE Original Reporting

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.