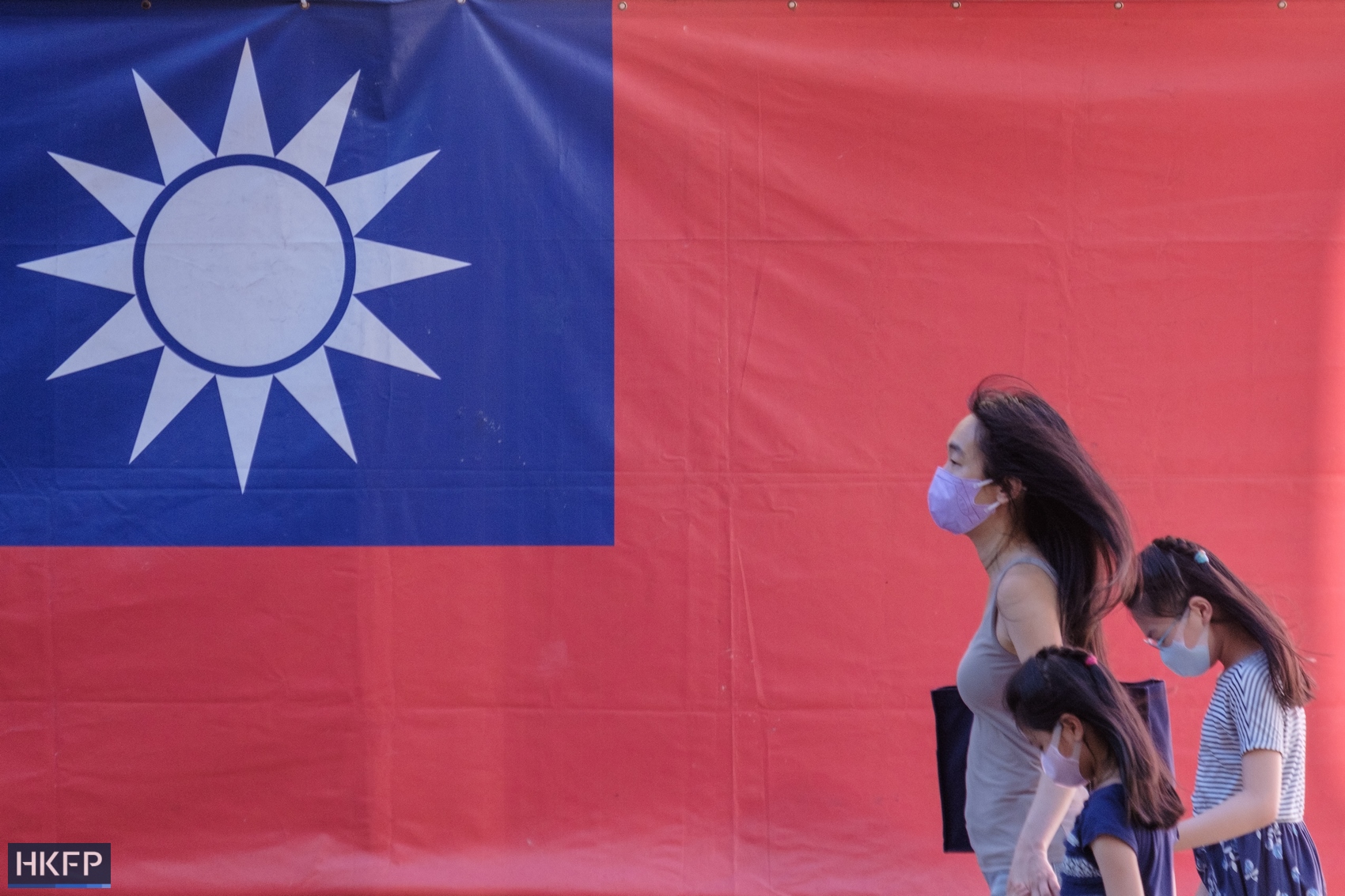

Taiwan has all the infrastructure of an independent country but only a dozen nations recognise it as such, with Beijing claiming it has sovereignty. The island’s status has been hotly contested for over 70 years and will again be a dominant topic as Taiwanese go the polls on Saturday to elect a new president and parliament.

In the media, Taiwan is often referred to as some combination of “self-ruled,” “democracy,” and “island” and even sometimes still as a “renegade province” – all turns of phrase used to avoid describing it as a country.

The technical reason for this is that only a dozen small countries and the Holy See officially recognise Taiwan, whose formal name is the Republic of China. Another reason is that Taiwan is claimed by the People’s Republic of China, although its Communist Party government in Beijing has never ruled the island.

Taiwan has many characteristics of a nation, such as a separate government, constitution, military, civil service, central bank, economy, legal system, education system, medical system, coast guard, legislature, language, diplomatic offices, and even an ethnic makeup distinct from China. But its status remains disputed.

Understanding why requires going back into the history of an island which is roughly half the size of Ireland but plays an outsize role on the world’s stage.

Who are the Taiwanese?

Taiwan’s first inhabitants were groups of Austronesian-speaking people – contrary to Sino-Tibetan Chinese – and culturally related to other ethnic groups in maritime Southeast Asia and the Pacific. One theory suggests that human migration into the Pacific may have started from Taiwan and in 2019 researchers successfully paddled a wooden dugout canoe from Taiwan to Japan’s Okinawa, testing out ancient maritime navigation techniques.

For thousands of years, Taiwan was home to varying indigenous groups until the early modern era and the expansion of trade and maritime activity in coastal Asia. Taiwan was conveniently sited between China and Japan, two of the great powers of the era, and was a convenient stopover point for fishermen and ships in need of fresh water and supplies or a hideout from the long arm of the law and imperial bureaucracy. Small informal settlements of Chinese, Japanese and other communities popped up on the west coast, where they traded with indigenous people. Portuguese traders named the island Formosa, a name still used today.

Enter the Dutch East India Company, also known as the “VOC,” who by the 1620s were expanding trade routes in Asia to capture the spice trade and help raise funds for religious wars back in Europe. The Dutch arrived in southern Taiwan in 1624, around the site of contemporary Tainan, where they set up their first colony to trade with indigenous people and also – they hoped – convert local indigenous and Chinese settlers to Christianity.

They also drafted in mainly male Chinese workers from nearby Fujian province on the mainland, setting in motion the widespread Chinese settlement of Taiwan. During this time, the Spanish also attempted for 20 years to colonise northern Taiwan but lost out to the Dutch.

By 1661, the Dutch were also expelled by the half-Chinese, half-Japanese “pirate king” Koxinga – allegedly due to office politics within the VOC that prevented them from receiving reinforcements from Indonesia. Taiwan was then briefly an independent kingdom before it was absorbed into China’s Qing Empire in 1683. Over the next two centuries, mainland Chinese would settle around half of Taiwan, mainly the plains of the west and north, while indigenous groups controlled the mountains and the east. The occasional European power like the Spanish and the French also tried to make inroads, but failed.

Edge of empire

From the 17th to the 19th century, Taiwan was a prefecture of Fujian province and did not become a full province of the Qing Empire until 1887. It had a reputation as an unruly place on the edge of empire, home to absentee landlords, clan infighting, and skirmishes with indigenous groups, who were gradually pushed off their land and into eastern Taiwan.

The chaotic environment has been described as “every three years an uprising, every five years a rebellion.” During this era, Taiwan also came to global attention due to the many shipwrecks around its southern coast and an incident in 1867 when American sailors from the Rover were killed by indigenous Taiwanese.

When the Qing Empire lost the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, after brief resistance from local Taiwanese and the Republic of Formosa, Taiwan was turned over to Japanese rule. Over the next 50 years, the Japanese unified the island and its geographical organisation today into counties still follows much of the Japanese model, including the decision to move the capital from sunny Tainan to rainy Taipei.

Japan left a lasting cultural imprint on Taiwanese culture and historical memory, as educated Taiwanese travelled there for work and study and adopted its customs.

The Japanese relationship with Indigenous Taiwanese varied depending on the ethnic group, with violent confrontations lasting until the 1930s in some parts. Practices such as facial tattooing were banned as Japan promoted cultural assimilation, although its anthropologists were also among the first to carry out major studies of indigenous Taiwanese culture. Despite the animosity, indigenous Taiwanese were also highly valued members of the Imperial Japanese army, deployed to places like the Philippines, Indonesia, and the Pacific. More can be read about this era in Outcasts of Empire: Japan’s rule on Taiwan’s “Savage Border.”

Over the three centuries from 1624 to 1945, Taiwan’s varying communities – Chinese, Japanese, indigenous groups and occasional Europeans or fellow Asians – intermarried, fought, and lived side by side. The next major migration followed the end of World War II and the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War. These people would collectively be known as the benshengren and yuanzhumin.

Post-war: where things get difficult

Much of the debate around Taiwan’s political status dates from the waning days of World War II, as the allies debated how to divide up Japan’s various colonial possessions. Since Taiwan was handed to the Japanese in 1895, the Qing Empire had fallen and China had become a republic, albeit not an entirely successful one.

The Republic of China’s Chiang Kai-shek wanted Taiwan (Formosa) returned to its control as stated in the 1943 Cairo Conference. The situation became more complicated, however, after the war ended and hostilities resumed between the ROC (Nationalist) and Communist forces.

Even as it began to lose the civil war in China, the ROC government took control of Taiwan in 1945 and staged a full-scale retreat there in 1949, taking with them the contents of the Forbidden City and two million soldiers and civilians. This group came to be called the waishengren, whose stories of exile were captured in Taipei People, a collection of 14 short stories. They would occupy most major government and elite positions for decades, dictating Taiwan’s China policy.

Even before their retreat to Taiwan, the Nationalists were not exactly popular. They viewed Taiwanese and the Japanese-speaking elite with suspicion while Taiwanese were incensed by the looting of much of the island’s infrastructure and industry to help fund the war effort, as described in Formosa Betrayed, the memoir of US diplomat George H. Kerr. Tensions boiled over into mass protests on February 28, 1947, a watershed moment in Taiwanese history. when thousands of civilians were killed by Nationalist troops.

The early years of the Chiang Kai-Shek regime were also marked by the beginning of the “White Terror,” nearly 40 years of martial law lasting from 1949 to 1987. This notably included the cultural assimilation of Taiwanese into classical Chinese culture and Chinese Mandarin. Amid this turbulent period, Japan formally signed the Treaty of San Francisco in 1951. Neither Beijing nor Taipei were invited, and Taiwan’s status remained ambiguous.

Even though the ROC government lost the Civil War, Cold War politics dictated that the US continue to prop it up against the communists as the sole representative of “China” – since Chiang had pledged to return there one day. As the years passed, this pledge became less and less credible and Taipei’s position representing “China” at the United Nations untenable.

The non-aligned movement of the 1950s and decolonisation in the 1960s also brought an influx of new members to the UN, many of them during the height of the Cold War more sympathetic towards Communist Beijing than to the US-backed authoritarian ROC. The decision by France to switch recognition to Beijing in 1964 is considered a watershed moment and many of its former colonies followed suit.

Does the UN recognise Taiwan?

In the 1970s, the question of what to do with the “China” seat at the UN became more and more pressing as it became abundantly clear that the ROC would not return to China, and that it was not appropriate for the Taipei government to represent a billion people in continental Asia. Several different proposals were floated until Resolution 2758 in 1971, “the Resolution on Admitting Peking” restored the rights of the People’s Republic of China as the “only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations.”

It did not specifically mention either the ROC or Taiwan, but instead said it would “expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.”

The final blow to an increasingly isolated Taiwan came in 1979, when the US – its most important ally – formally severed ties and recognised Beijing.

This decision, however, came with a very large asterisk attached – the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act that allowed the US to continue an informal relationship and military sales. The Act does not promise that the US will defend Taiwan, but instead says it will “make available to Taiwan such defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability.”

Over the years more legislation has followed, allowing for more unofficial contact between high-ranking US and Taiwanese officials and similar measures.

Since it was expelled from the UN, Taiwan has been able to participate at times as an “observer” at the World Health Organization, but this typically depends on which party is in office. Since the Democratic Progressive Party – seen by Beijing as separatists – took power in 2016, Taiwan has been banned from events including the World Health Assembly. It is not allowed to use the name “Taiwan” or “ROC” at international events like the Olympics, where it uses “Chinese Taipei” to compete separately. The World Trade Organization uses the name “The Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu.”

What is ‘strategic ambiguity’?

How Taiwan and its relationship with China is defined varies depending on country, although Beijing argues that its definition is the only correct one.

Beijing’s “One China Principle” says there is a single sovereign state known as China and Taiwan is an inalienable part of that country. This is not to be confused with the US “One China Policy,” which recognises the People’s Republic of China and acknowledges that Beijing claims Taiwan, but does not endorse that claim, according to the Brookings Institution.

While two definitions of “One China” are mentioned the most frequently in the media, every country has its own specifically worded policy. The differences may be granular, but they are important and are listed in a chart compiled by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Some definitions specifically mention China’s sovereignty over Taiwan, while others simply acknowledge or respect – without comment – the fact that Beijing has such a claim. The vagueness on Taiwan policy is a deliberate diplomatic decision. The US even has a term for it: “strategic ambiguity.”

In Taiwan, which is still formally known as the “Republic of China,” there is a similar degree of vagueness to avoid provoking Beijing while not submitting to its territorial claims.

It is widely agreed in Taiwan that if the government were to change its name to simply “Taiwan” or declare “independence” from China, Beijing would attack.

Many Taiwanese, however, including the Democratic Progressive Party would say none of this is necessary because Taiwan is already de facto independent. In Taiwan, you typically hear this position referred to as “the status quo” or “maintaining the status quo.” Few people support formal independence because it would likely mean war, but few people support unification or “moving towards unification,” according to polling by National Chengchi University.

The few who do support unification are typically older people who want unification under a government other than the Communist Party.

More can be read about hair-splitting over so-called policies like the “1992 Consensus” between the Kuomintang and Beijing, but in practice they all generally concern ways of allowing Taipei to engage with Beijing while not officially submitting to it. Some changes have been made, however. While Taiwan has retained the official 1946 ROC constitution, the document has been amended over the years to (arguably) only refer to Taiwan and its many outlying islands and not to China proper, according to Taiwan expert Nathan Batto on his blog Frozen Garlic.

Why is Taiwan’s status still a big deal?

Taiwan’s political status has become a more pressing issue because of major changes over the past 30 years. From a single-party authoritarian state which spent nearly 40 years under martial law ending in 1987, the island began a process of democratisation concluding in the first direct president election in 1996. It became one of the most successful members of the 1990s graduating class of “third wave democracies.”

Social change has followed political change over the past 30 years, with Taiwan notably becoming the first place in Asia to legalise same-sex marriage. During this time, Taiwanese identity has also slowly solidified as the distinctions between its historic groups like waishengren and benshengren have fallen away.

While many Taiwanese might acknowledge they are culturally and historically linked to China or feel a great affinity for it, they are also now “Taiwanese.” This change has also led to reassessment of Taiwanese history and culture, particularly its indigenous past.

Meanwhile, 1990s predictions that China would liberalise as it grew richer have turned out to be wishful thinking and it has become increasingly authoritarian. The awkward contrast between Taiwan and China has also become apparent to some Western governments, which purport to support “democracy” but do not acknowledge one of Asia’s more successful examples of it. On a more pragmatic level, many countries want to engage with Taiwan and its cutting-edge semiconductor industry, so there has been an uptick in unofficial engagement.

Whether this will lead to the acknowledgement of Taiwan as a “country” is still far in the future, as China has been known to punish countries like Lithuania that publicly became too close too fast with Taiwan. It’s also the world’s second-largest economy with the world’s largest military, and this reality means pushback on any of its positions is unlikely.

Dateline:

Taipei, Taiwan

Type of Story: Explainer

Provides context or background, definition and detail on a specific topic.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

Original reporting on HKFP is backed by our monthly contributors.

Almost 1,000 HKFP Patrons made this coverage possible. Each contributes an average of HK$200/month to support our award-winning original reporting, keeping the city’s only independent English-language outlet free-to-access for all. Three reasons to join us:

- 🔎 Transparent & efficient: As a non-profit, we are externally audited each year, publishing our income/outgoings annually, as the city’s most transparent news outlet.

- 🔒 Accurate & accountable: Our reporting is governed by a strict Ethics Code. We are 100% independent, and not answerable to any tycoon, mainland owners or shareholders. Check out our latest Annual Report, and help support press freedom.

- 💰 It’s fast, secure & easy: We accept most payment methods – cancel anytime, and receive a free tote bag and pen if you contribute HK$150/month or more.

MORE Original Reporting

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.