Part of HKFP’s Shifting Narratives series.

Hong Kong’s umbrella pro-democracy protest coalition the Civil Human Rights Front announced its final shut down on Sunday. The decision to draw the curtain came after the city’s police chief said some protests it organised in recent years may have violated the national security law, even though the group had – for years – cooperated with the force in organising peaceful mass marches. A former chief executive once even referred to its members as “friends.”

Police chief Raymond Siu warned during an interview with Ta Kung Pao on Friday that police had gathered all evidence necessary “to take action against the illegal organisation anytime.” His warning came even though the group had not organised any protests since the national security law’s enactment last July. The city’s chief executive Carrie Lam once told the UN that it was not retroactive.

Back in May, police said that they wanted to quiz Front organisers about their alleged failure to register under the Societies Ordinance, and also sought details of past activities and funding sources. Dozens of its member groups quit as a result. Its last remaining spokesperson Figo Chan was sentenced to 18 months behind bars at the end of May, after admitting to offences related to the 2019 protests.

By June, the CHRF announced this year’s annual July 1 pro-democracy march was be cancelled, adding that it was considering whether to disband.

Applications by three other pro-democracy groups to hold July 1 demonstrations were struck down by police, with the demonstration banned for the second year in a row.

But current Chief Executive Carrie Lam, her predecessors and government spokespersons routinely over the years referred to demonstrations organised by the Front in press releases immediately after the events ended. HKFP reviewed these statements from 2003 until today to see how the government’s attitude changed.

The Front was formed in 2002 to coordinate protests by a network of pro-democracy or social issues advocacy groups in the city. It held its first rally in December that year in response to the government’s proposal to pass a new national security law as required by Article 23 of the Basic Law. On July 1, 2003, some 500,000 people took part in a rally organised by the Front to protest against the bill.

As soon as the rally was over, the then-chief executive Tung Chee-Hwa issued a statement saying that he was “very concerned” by the turnout, and “expressed his understanding of the aspirations of the participants.” The government “understood fully the importance the community attached to their rights and freedoms.”

Under public pressure, Tung’s government retracted the Article 23 proposal two months later.

The Front became lead organiser for most of the city’s largest marches and assemblies in subsequent years, including those held annually on January 1 and July 1. Ahead of these events, Front convenors and representatives typically met police and sports facility authorities to negotiate arrangements and terms – such as temporary traffic rerouting or access to Victoria Park’s football pitches, the usual starting point for big marches. The Front has never in its history held protests that did not receive a police-issued “non-objection letter.”

After the July 1 march in 2004, Tung again addressed those who took part. “I clearly hear your views. I understand your aspirations,” he said in a statement. “We are grateful for the advice.”

Listening humbly to the people

As New Year’s Day and July 1 marches became part of the political tradition, the government routinely responded to them in its press releases.

Until 2013, all of these statements followed a similar structure. They typically acknowledged the protests, responded to core issues championed by protesters, and ended by acknowledging other smaller, “different” protest demands.

“The SAR Government fully respected people’s rights to take part in processions and their freedom of expression,” these statements began by saying. Between 2009 and 2013, the spokesperson also vowed to listen to the public’s views “in a humble manner.”

After the July 1 march in 2013, the then-chief executive Leung Chun-ying even addressed Front representatives as his “friends.”

“Friends from CHRF who hosted this protest, other friends who participated in organising it, as well as Hongkongers who attended the demonstration… You’ve worked hard. The government will carefully listen to all demands expressed in the protest,” he said.

In December 2013, Hong Kong geared up for yet another round of political reform to democratise the city’s legislative and leadership elections as required by the Basic Law, after critics had described previous reforms as too conservative. A law professor at the University of Hong Kong, Benny Tai, proposed a mass civil disobedience campaign to occupy the city’s roads in an attempt to force authorities to respond to public demands for universal suffrage in the chief executive elections.

Protest legally

Amid rising discontent about the slow progress towards democracy, the July 1 march in 2014 saw a record turnout of 510,000 people, according to the organisers’ estimates. While Tai’s plan did not begin until almost three months later, the July 1 event was seen by student activists as a dress rehearsal, with hundreds occupying Chater Road overnight in an unauthorised sit-in. Over 500 were arrested, including the Front convenor Johnson Yeung.

In its usual statement in response to the protests, the government spokesperson maintained that it respected Hongkongers’ freedoms – “via legal channels and in a peaceful manner.”

“Any contravention of the law and breach of public order” will be handled by police “in accordance with the law,” the spokesperson’s statement read.

The 2014 Umbrella Movement unfolded in late September, after Beijing announced tight controls on who could stand in upcoming chief executive elections. Thousands occupied roads around the legislature and in two other key districts following a student sit-in, in a 79-day civil disobedience campaign originally conceived as “Occupy Central.” Leading figures in the largely peaceful movement were jailed in the years following the police clearance.

After the 2014 protests ended, the government stopped saying in statements that it respected residents’ freedom of expression, until the formula was picked up again in 2019. Instead, it sometimes used its statements to counter protesters’ demands.

In 2015, for example, the government spokesperson said demands to remove current requirements for the chief executive election by amending the Basic Law “would absolutely not be conducive” to Hong Kong’s interests.

In 2016, the government spokesperson said it “[took] note of different views” expressed in the July 1 protest and “[hoped] that various sectors will… strive to seek common ground.” After another protest organised by the Front in August, the government spokesperson said those “who held different views… should abide by the spirit of the rule of law.”

In the two subsequent years, the spokesperson reiterated the official position on political and economic reforms in statements responding to the July 1 protests. But in 2018, it condemned protesters for using slogans that “disrespect ‘one country’,” calling them “sensational and misleading.”

The Front saw the smallest march in its history on January 1, 2019, with a turnout of only 5,500. The government reverted to its earlier statements, saying it “fully [respected]” Hongkongers’ right to participate in processions, but issued a separate statement saying that it “seriously condemns” the use of slogans advocating Hong Kong’s independence.

“The spokesman expressed deep regret that the organiser has not appealed to participants not to conduct any activity that contravenes the laws in force in the HKSAR, including the Basic Law,” it read.

Widespread protests against a bill which would have allowed extradition to China erupted in summer 2019. As the Front held its July 1 rally that year in Central, other protesters stormed the Legislative Council. “The Government always respects the public’s freedoms and rights of assembly,” its statement read. “It also understands that people have different views on Government policies.”

The 2020 January 1 rally would prove to be the Front’s last. The government described protesters as “lawful, peaceful and rational” and said it would “humbly listen” to their views.

But the Front’s application to organise a march on July 1 that year was rejected, with Covid-19 restrictions cited as a reason.

On March 5, a Singapore media report citing anonymous sources which claimed the Front was under national security investigation prompted a mini-exodus from its ranks, with at least six pro-democracy parties or groups announcing their departure from the coalition.

With pro-democracy political leaders behind bars over offences related to the 2019 protests or on national security charges, the Front faced renewed attacks from the China-owned press in Hong Kong that month, including from Wen Wei Po and Ta Kung Pao.

In an article headlined “Why hasn’t the CHRF been banned after operating illegally for 19 years?” Ta Kung Pao questioned the group’s legality, saying it is was not registered as an entity under the Societies Ordinance.

Police told the Front in April that it was suspected to have run afoul of the law by not registering under the ordinance. This was even though officers had for years met representatives of the group to make arrangements for the protests, and the government had routinely acknowledged the demonstrations.

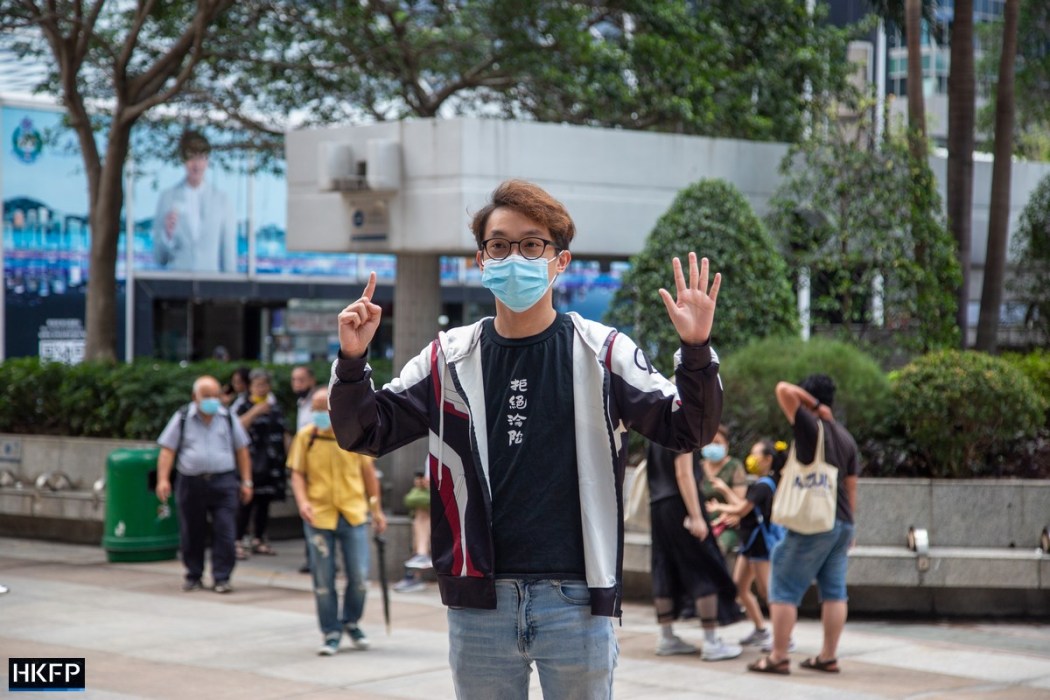

The Front’s former convenor and one of its last remaining members, Figo Chan, refused to comply with requests for information. Chan was sentenced to 18 months in prison in May, after he pleaded guilty to organising an unauthorised National Day protest in 2019.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.