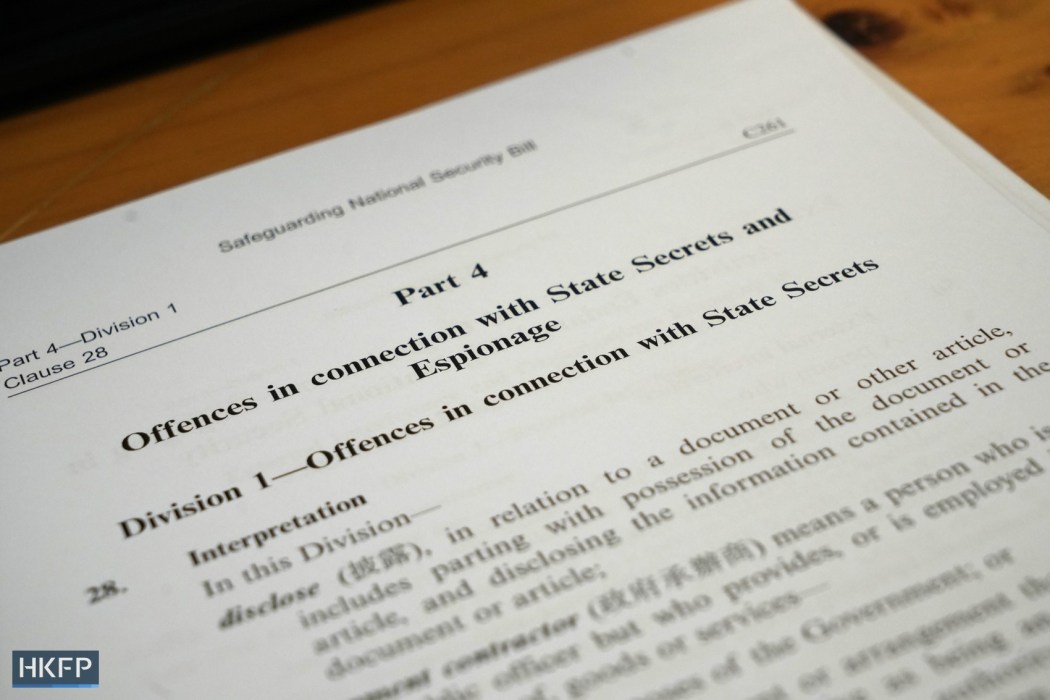

Hong Kong’s homegrown security law would include a public interest defence for certain offences related to the theft of state secrets, a draft of the proposed legislation has revealed.

According to the draft bill published on Friday morning, a person facing charges under three types of state secrets offences – unlawful acquisition, unlawful possession and unlawful disclosure – may invoke the defence that they had made “a specified disclosure.”

The bill defines a “specified disclosure” as one where the purpose of the disclosure is to reveal a threat to public order, safety, or health; that the government is not functioning lawfully; and where the “public interest served by making the disclosure manifestly outweighs the public interest served by not making the disclosure.”

The draft of the city’s homegrown security law was brought to the Legislative Council for discussion on Friday.

Article 23 of the Basic Law states that Hong Kong must enact its own laws to criminalise acts that endanger national security. Colloquially known as Article 23, the homegrown law is separate from the Beijing-imposed national security legislation, which was enacted in 2020 following the 2019 protests and unrest.

During the one-month consultation period for the security law, suggestions were raised that leaks believed to be made in the public’s interest should be exempted from prosecution. Secretary for Security Chris Tang said the government would consider it.

The draft of the Safeguarding National Security Bill, however, did not state public interest exemptions for offences involving the unlawful possession of state secrets when leaving Hong Kong, unlawful disclosure of information acquired by espionage, and unlawful disclosure of information that appears to be confidential matter.

Under the unlawful disclosure of state secrets offence, the public interest exemption did not appear under a section of the draft related to the unlawful disclosure of state secrets made by a public officer or government contractor.

Press freedom concerns

State secrets, according to the draft bill, includes secrets concerning “major policy decision on affairs” relating to China and Hong Kong; the construction of China’s national defence; the economic and technological development of China and Hong Kong; and the relationship between the central and Hong Kong governments.

Under the unlawful acquisition of state secrets offence, “acquiring” information involves “collecting, recording or copying,” but not information that came into someone’s possession without their knowledge or without them “taking any step.”

For the unlawful disclosure of information that appears to be confidential, people can be convicted regardless of whether the information is true or not.

Earlier, the Hong Kong Journalists Association expressed concern about the theft of state secrets offence, calling the definition of “state secrets” laid out in a public consultation paper for the law too broad. Journalists receive leaks from government sources on occasion, for example in relation to personnel changes and policy announcements, and it was difficult for the press to determine whether their sources were disclosing this information with lawful authority, the group said.

The draft of the homegrown security law does not state any protections for journalists.

Up to 10 years’ jail

Those convicted of the unlawful possession of state secrets face up to five years in jail, while those convicted of unlawful disclosure of information acquired by espionage face up to 10 years in jail, according to the draft bill.

Unlawful acquisition of state secrets may carry a maximum sentence of seven years, the document states.

The introduction of the bill came just nine days after the end of a one-month public consultation period, which prompted more than 13,000 submissions, 97 per cent of which expressed support for the new security law, according to the government.

Submissions that opposed the proposals included those from “anti-China organisations” based overseas such as Amnesty International and Hong Kong Watch, the government said in a summary of the views collected during the consultation.

Locally, opposition to Article 23 has been muted, with the pro-democracy League of Social Democrats among the few groups to express their concerns that its legislation could have a negative impact on freedoms. The city has not seen mass protests since Beijing imposed the national security law, under which dozens of civil society groups have collapsed and activists arrested.

In 2003, the last time Hong Kong attempted to legislate Article 23, an estimated 500,000 protesters marched to oppose the law.

Article 23 security law bill in full:

- Hong Kong proposes dissolving organisations accused of ‘external interference’

- Threshold for early release may be raised for national security prisoners, draft bill says

- Hong Kong proposes life sentences for treason, insurrection, sabotage

- New powers mulled for police, courts to limit nat. security detainees’ access to lawyers

- Hong Kong proposes cancelling ‘absconders’ passports under new security law

- Public interest defence proposed for some ‘state secrets’ offences in draft security law

- Hong Kong proposes raising max. penalty for sedition to 10 years under new sec. law

- Courts could extend detention without charge for 2 weeks, draft nat. sec. bill suggests

- Hongkongers may face 7 years jail for ‘inciting disaffection’ of public officers

- Hong Kong’s business community expresses concern over proposed new security law

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.