Election campaigns and their enthusiasts everywhere are always full of extravagant promises and idealistic goals. Hong Kong is no exception — even under its new national security regime and the revamped election system designed to keep everyone but “safe” patriots out of the competition.

Under these circumstances, the much-repeated aim of “bringing us together” — against the backdrop of “national security” — might seem to the uninitiated like mission impossible. But these objectives headed the wish list for enthusiasts and well-wishers as soon as John Lee Ka-chiu emerged in early April as the candidate-in-waiting for Hong Kong’s top job.

His promoters naturally don’t admit as much, but the twin goals of civic unity and national

security will be achievable only via the same sleight-of-hand that is now making it possible for officials to claim nothing of any political significance has changed here since Beijing promulgated the National Security Law for Hong Kong on June 30, 2020.

In this way, Hong Kong’s revamped election system, promulgated by directive from Beijing in early 2021, is officially said to leave all the old promises intact: universal suffrage, one-country-two systems, autonomy, Hong Kongers in charge of Hong Kong, and so on.

It’s just that the names remain unchanged. But new national security definitions have been substituted for all the promises as they were originally understood.

Similarly, it’s only in this new re-defined post-June 2020 universe that the eager calls for John Lee to govern a politically divided city by bringing Hong Kongers together makes sense. But then, election campaign rhetoric everywhere is always an improbable mix of exuberance and prevarication.

The new candor

Despite much speculation during the past two years about possible successors for the current unpopular Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, Beijing’s endorsement of John Lee in early April came as an almost complete surprise. He had not been among those most frequently mentioned for consideration.

This was despite his meteoric rise from the ranks of Hong Kong’s police force to become the government minister responsible for security (2017-2021) and then, in June 2021, Chief Secretary or the Number Two official, second only to Carrie Lam, in Hong Kong’s governing hierarchy. Maybe the possibility was automatically discounted because Hong Kong had never had so direct a link between its top government official and law enforcement.

But at least Hong Kong had fair warning that the decision would be made first in Beijing and then with the Election Committee nomination and selection formalities proceeding afterward in Hong Kong.

This selective candour is another feature of the new national security regime, that has taken shape here since June 30, 2020. Beijing is making the rules and Beijing is deciding up front who will be Hong Kong’s next Chief Executive. No more niceties about public opinion, consultations, and the like. There must be no doubt as to the source of authority for this decision.

The message is especially for the benefit of local “separatists” and those who hanker after “independence” from Beijing’s decision-making authority. They must abandon their illusions about localism and autonomy, however defined, especially if it means contributing to the choice of candidates for the post of Chief Executive.

Long assumed but never authoritatively acknowledged in so many words, the sequence of Beijing decision-making on the choice of Chief Executive was acknowledged in unusually frank comments by Hong Kong’s veteran pro-Beijing politician Jasper Tsang Yok-sing during a TVB Straight Talk interview last December 28.

Tsang did not discuss the pre- June 2020 election formalities but said what had been assumed even then: Beijing would be first to make the decision on its choice for Chief Executive, with the endorsements and authentication procedures then following in Hong Kong to signify public recognition and acceptance.

These formalities are nevertheless very elaborate. They include the election of a 1,500-member Election Committee. It’s five-sector design remains more-or-less the same as that of the previous pre-2021 committee: business, industry, and banking; white collar, professionals; grassroots, labour; Legislative Councillors and others; Hong Kong delegates to national representative bodies and other national organizations.

But the qualifications for admission to each of the sectors and the subsectors within them underwent substantial revision as part of the 2021 election system overhaul. Hence the 1,500-member Election Committee is now weighted entirely in the “patriots only” direction, instead of only predominantly as before. Its membership was confirmed in an election held last September.

Committee members must formally nominate a Chief Executive candidate by way of their

endorsement signatures. An aspiring candidate must receive the signatures of at least 188 Election Committee members, with at least 15 signatures coming from each of the five main Election Committee sectors. But as the only contender, Lee had no competition. He garnered 786 signatures.

There had been a few others who tried throwing their hats in the ring but once Bejing’s

endorsement of Lee was made clear, the others did not proceed with their campaigns.

Finally, the Election Committee must confirm the candidate with a formal vote.

This is scheduled to take place on Sunday. Officially, the number of votes required to win is 750, or half the full complement of 1,500 Election Committee members. In fact, the number of committee members actually voting will not be 1,500, but only 1,462. This number was provided by Hong Kong’s Registration and Electoral Office in an e-mail message dated March 7, 2022. There are different calculations and the number continues to fluctuate.

The number does not add up to 1,500 due to the practice of concurrent positions or in this case dual eligibilities. For example, Michael Tien Puk-sun qualifies for one Election Committee seat because of his membership in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council and another seat as a member of Hong Kong’s National People’s Congress delegation. But on May 8, he will only be allowed to cast one vote, not one vote for each of the seats he is qualified to occupy. Nevertheless, the specified number of votes needed to win is still 750.

Flashback

A short glance back at the recent past might be in order here to remind everyone about just how far removed the present new routines are. The comparison is not so much between those existing before June 2020 since the Election Committee format is essentially the same.

The aim is only to remember what Hong Kong democracy campaigners had been trying to

achieve since they first read Beijing’s promises as originally written down in the Basic Law. This document was drafted under Beijing’s supervision and promulgated in 1990, to serve as Hong Kong’s post-1997 constitution.

The Basic Law (Articles 45 and 68) promised that the Chief Executive and all members of the Legislative Council would eventually be elected by universal suffrage. In terms of chronology, as mandated by Beijing, the first post-1997 opportunity for this initiative to begin was the 2017 election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive.

But Beijing’s August 31, 2014 decision wrote an end to that possibility by specifying conditions for the first 2017 “universal suffrage election” that would have left the general public no choice but to endorse Beijing-approved candidates. That was also Beijing’s final word on its original universal suffrage promise for Hong Kong’s Chief Executives. There was no suggestion of further adjustments in later years.

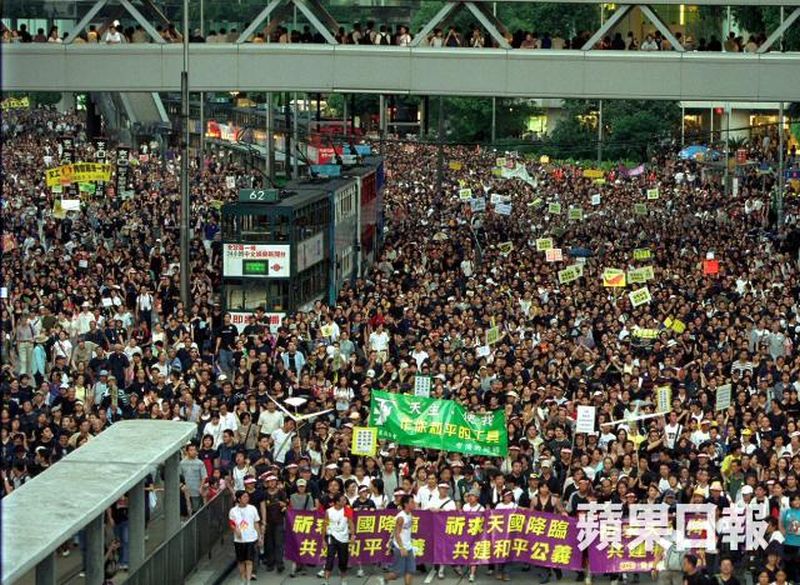

It was the shock of that August 31, 2014 Decision — when campaigners had been primed for a “genuine” election — that precipitated the 79-day street blockades known as Hong Kong’s Umbrella-Occupy Movement. Campaigning and public consultations had gone on for months beforehand, with all kinds of ideas circulating to try and guarantee a “genuine” universal suffrage election with “genuine” candidates produced by some sort of popular candidate nominations beforehand.

The rest of the story is well-known. Pro-democracy legislators refused to endorse the design for the 2017 Chief Executive election based on Beijing’s August 31 Decision. The resistance movement escalated thereafter — culminating in Beijing’s June 2020 decision to call time, declare them all subversives and separatists bent on provoking a “colour” revolution, and put an end to the post 1997 promise of universal suffrage elections that campaigners had insisted on defining as “genuine” universal suffrage.

John Lee emerges

The “announcement” of John Lee’s candidacy was never conveyed to the public as such. Instead, the public came to know by way of news reports that Lee was preparing to begin the formalities necessary to register his candidacy.

Soon after this information appeared, and following months of silence on the matter, the

incumbent Carrie Lam finally announced that she would not be seeking a second term. Beijing’s decision for Hong Kong’s next Chief Executive had been made behind closed doors and was never even conveyed to the public in so many words. John Lee simply took his place in the course of several news reports as the leader-in-waiting.

The scene stood in stark contrast to the demands for public participation and the popular

nomination of candidates that characterized the reform campaigns of earlier years, and even previous Chief Executive election routines themselves.

In 2012, pro-democracy campaigners sponsored their own mock primary election exercise to select their preferred Chief Executive candidate. Polling “booths” were set up on street corners and the Democratic Party’s Albert Ho was selected as a candidate in this way. He then went on to win 76 votes from the Election Committee since the old pre-2020 Election Committee, unlike its successor, had a minority of pro-democracy members.

That same year, popular enthusiasm — or lack of it — also seemed to play a role in “defeating” Beijing’s presumed preferred candidate for Chief Executive, the lacklustre Henry Tang. Leung Chun-ying was the beneficiary. The 2012 Election Committee vote count was: CY Leung, 689; Henry Tang, 285; Albert Ho, 76.

In 2017, much energy and enthusiasm among pro-democracy Election Committee members went into the campaign of candidate John Tsang. The idea behind these mock election exercises was to use whatever opportunities existed within the system in order to try and maintain public interest and keep up popular pressure for ongoing reforms — even in the face of Beijing’s continuing intransigence and refusal re-visit its August 31, 2014 decision.

Big names rally round John Lee

In contrast, John Lee’s way was laid out before him and all he had to do was follow the

prescribed markers along the route. Known locally as “heavyweights,” political and business leaders immediately came forward to declare for Lee — after a meeting at Beijing’s representative Liaison Office here. They included those who had participated in the selection formalities of both Carrie Lam in 2017, and Leung Chun-ying in 2012.

A campaign office was soon up and running, headed by veteran pro-Beijing politician Tam Yiu-chung. He is Hong Kong’s current representative on the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing.

Once again, as during the Legislative Council election last year, Beijing’s Liaison Office personnel — no longer working behind the scenes as they reputedly did before 2020 — are now serving as overall coordinators and campaign managers. Their aim: to convey a message of unified support for the candidate.

“Sources” have been reporting for months that Beijing is keen to avoid any appearance of infighting or discord within the pro-Beijing political establishment – such as that in 2012 between Henry Tang and Leung Chun-ying.

Mission impossible?

The initial euphoria seemed to know no bounds. Lee himself issued a statement saying he had been in government for 40 years and knew that serving the people of Hong Kong was a glorious endeavour. His mandate in this setting nevertheless derived from Beijing not Hong Kong. Cited as the authority in this respect was Xia Baolong, who heads the central government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office in Beijing.

The reference was from a much-quoted speech Xia gave last summer to mark the one-year anniversary of Hong Kong’s National Security Law. Xia had spelled out the five qualities now expected of those who administer Hong Kong under the new “patriots only” mandate.

At the time, in July 2021, Hong Kong was preparing for the first sequence of elections under the newly re-vamped system: the Chief Executive Election Committee election in September; the Legislative Council election last December; and finally, the coming May 8 election for Chief Executive.

Xia enumerated five qualities expected of all who entered Hong Kong’s new “patriots only” governing establishment via these elections. First and foremost, would be to safeguard national security; next, address Hong Kong’s deep-seated problems. His third point was to serve the people; fourth was to unite all sectors of society; and finally, don’t sluff off, be diligent in work.

Xia’s emphasis on national security was explained in terms of Hong Kong’s “anti-China”

troublemakers. They had tried to carry out a local version of the Western-backed “color

revolutions” that led to the 1989-91 break-up of the Soviet Union, when its Communist Party red went out of fashion.

Xia had harsh words for Hong Kong’s troublemakers, giving no quarter and without any

recognition of the differences that had existed between and among them: moderates, localists, separatists, independence advocates, and so on. Xia called it an iron rule and said diligence must be maintained throughout the electoral process to ensure that all loopholes are plugged. Such people must not be allowed to enter.

He was quoted as saying that anti-China disrupters must never be allowed anywhere near Hong Kong’s governing establishment or in mainland terminology its administrative structures. Hong Kongers only administer their territory, which is governed by Beijing. This began to be a sensitive point for Beijing after officials decided that perhaps the Basic Law’s promises about autonomy had given people the wrong impression about just how far the promises were intended to go.

A manifesto for all walks of life… but not for all political seasons

Issued on April 29, Lee’s 44-page election Manifesto followed the spirit of Xia Baolong’s

guidelines — with the exception of Xia’s focus on the need to keep “anti-China” troublemakers as far away from Hong Kong’s governing institutions as possible.

This exception, in fact, represented the sleight-of-hand manoeuvre that signified “anti-China” troublemakers could now be ignored because they had been completely removed from the political scene and no longer signified one way or the other.

The manifesto does promise, however, that Lee’s administration will pass the controversial Article 23 legislation. This has been resting on the Legislative Council’s shelf since 2003. That was when Hong Kong’s first big post-1997 mass demonstration protested, on July 1, 2003, what was then thought to be the imminent passage of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, Article 23 mandate.

The Basic Law’s Article 23 requires the city to pass its own legislation against treason, secession, sedition, and subversion against the central government, plus theft of state secrets, and interference by foreign political organizations.

Otherwise, Lee’s manifesto mostly avoided politically divisive topics whether to identify them or suggest how the political divisions growing since Hong Kong’s 1997 return to Chinese rule might be addressed to reduce tensions. Instead, the manifesto is presented as an extended sequence of generalities with a series of principles and pledges.

These are introduced as the Four Tenets of Our Vision: (1) Strengthen governance to tackle livelihood problems. Article 23 legislation will contribute to this aim. (2) Streamline bureaucratic procedures and provide more housing for a better living environment. (3) Enhance overall competitiveness and pursue sustainable development. (4) Build a caring and inclusive society and enhance upward mobility for young people. This last is a favourite theme in official circles. Social and economic inequality is thought to explain Hong Kong’s dissident youth culture.

One controversial political initiative was nevertheless slipped in: Lee aims to enhance national education to raise the sense of national consciousness and identity among Hong Kong students. This was the curricular reform shelved in 2012 after protests by parents, teachers, and students.

At a later televised conference call, Lee took questions from journalists and selected local residents. Asked if he would restart the government’s abortive attempt at introducing universal suffrage elections, he said no way. The newly revamped post-2020 electoral system was only just about to be completed and time would be needed for the new system to demonstrate its ability to produce good governance.

Reactions were naturally subdued. No one wants to risk making critical potentially seditious remarks about the new Chief Executive, sedition being a new area of interest for Hong Kong’s national security police. Official announcements during the past year as implementation of the new National Security Law progressed nevertheless remain a source of concern with only uncertainty as to what lies ahead.

The return of Article 23 to the Legislative Council’s agenda was actually announced months ago. Draft legislation is due to be tabled later this year. The question is why Hong Kong needs another security law when the June 2020 version seems to be humming along nicely and covering all possibilities.

The reply, given by newly appointed Secretary for Security Chris Tang Ping-keung, also a law enforcement veteran, was that the new legislation should focus on updating Hong Kong’s old colonial era Official Secrets Ordinance.

This seemed a long shot, but Tang explained the thinking behind it. He said foreign countries were using Hong Kong for activities that threatened national security. This they were doing by provoking “colour revolutions” in the manner of the 2019 street protests. As he explained it, espionage activities included seditious acts such as inciting hatred of the government and the use of violence in order to seize political power.

Tang had earlier pointed to the organisation of protests in 2019 when demonstrators all arrived at the same locations with the same gear: helmets, black T-shirts, and so on. Plus he had noted the enthusiastic coverage by the foreign media. From all this, he deduced that the 2019 protests must be the result of foreign state-level actors since Hong Kongers acting alone would not be able to exert that degree of influence. Hong Kong therefore needed a law to safeguard against such threats.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.