A little known fact about San Po Kong, an area whose industrial soul is slowly being chipped away as nearby Kai Tak is redeveloped, is that it is home to a cave. Two caves, if we are being generous.

The second exists in abstract form at Fung Tak Park, a government-owned public space on the district’s fringes that – with some imagination – recalls the 16th-century Chinese novel Journey to the West. In the story, Sun Wukong, perhaps better known as the Monkey King, made his home in a cave behind a waterfall. And in the park, a wall of water pours from an artificial rock formation, through which people walk to enter the so-called Monkey King’s Paradise.

The other, more fully formed and immersive cave lies 17 floors above ground in an otherwise nondescript industrial block. Like the Monkey King’s cave, it is guarded by a waterfall of sorts. However, the character it houses – the “tiger daughter” – comes not from centuries-old Chinese mythology but from the imagination of Hong Kong artist Vaevae Chan.

After years of “digging,” creating and waiting, Chan’s cave opened to the public on February 17. The interactive, walk-through art installation spans several spaces: a lifelike cave rendered dreamlike through a collection of ceramics and found objects; a space for sculpture that is otherwise almost completely void of light and texture; and a screening room where the viewer is invited to take a seat and surrender to the fantastical tale of the cave, the things within it and the tiger daughter via the medium of video.

‘Might as well go inward’

Originally a ceramic sculptor, Chan’s cave was borne of trauma – hers and Hong Kong’s. In 2018, her father died suddenly. The following year, she watched as her hometown was wracked by protests that began peacefully but often descended into violence. “Everybody kind of felt very helpless, I remember that feeling,” she tells HKFP from her San Po Kong studio, a celebration of space, colour, and objects.

Dressed almost completely in black, apart from the print on her t-shirt and scarlet-coloured socks, Chan appears entirely at home amid the riotous assembly of items on display. Slight but certain, she is an enthralling storyteller.

“I know every angle, every corner… And I spent a lot of alone time there, but I talked to the cave… I named this cave Uncle Cave, and it’s like a cave who is accompanying me, like Uncle Guan.”

Vaevae Chan

She recalls following the news throughout the city’s months-long unrest, and finding different outlets’ reports so conflicting that she did not know what to believe. “I started asking what was real,” Chan says.

“I remember being here one day and looking around and saying to myself: ‘what is most real to me is the world that I built with my hands for myself in front of my eyes’… So, instead of finding truth in the outer world, I decided [I]… might as well go inward.”

In a way, Chan’s cave is built of grief. Throughout the year-long process of what she calls “sculpting space,” she took her grief and packed it tightly into the cave’s walls and crevices, relieving herself ever so slightly of its burden in the process.

“I know every angle, every corner,” Chan says. “And I spent a lot of alone time there… I talked to the cave… I named this cave Uncle Cave, and it’s like a cave who is accompanying me, like Uncle Guan,” she adds, referring to the Chinese god of war Guan Yu, the people’s deity during Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella Movement.

She mentions a scene from the 79-day pro-democracy civil disobedience campaign, when a shrine to Guan Yu sprung up in the centre of Nathan Road. Although Guan Yu is, objectively speaking, “just a statue,” Chan says, it also has “an invisible existence or a collective consciousness.”

Protesters respected and guarded the Guan Yu statue in the middle of Nathan Road, until it was eventually cleared away by police. “This is the power of the invisible spirit,” Chan says, “it is humans – our thoughts, our wishes – that make the god what it is.”

She continues: “So, I believe that every object has a soul, and deserves to be treated in the way we would treat people… the spiritual value is a lot greater that the physical value.”

Guan Yu is among the 90-odd objects that line the walls of the cave. Ceramic buns that Chan has made sit next to seemingly random items from Chan’s extensive collection. “I have a lot of collectibles… I have a connection with different objects, and I believe every object has a soul,” Chan says.

“I felt like placing them in the cave around me would allow people to see them in a different aspect, a different way,” she continues.

But it took some time for her found objects to find their way to the installation. “After I completed the cave, I was like: ‘why am I doing this? What am I doing?’ I feel like the healing process got to a point where I was asking and knowing a lot about myself,” Chan says.

It was time for the artist to look outward once again. “Interestingly, there were a couple of events that happened, things that I encountered, that led me to find out the answer,” she says, “and that has to do with Tiger Balm Mansion, with Mr Tiger.”

Mr Tiger’s guidance

In 2018, before her father died and before the protests – before Chan even had the space that would become the cave – she went to Singapore to visit Haw Par Villa, an eclectic theme park once owned by Aw Boon Haw, the eccentric Tiger Balm magnate, also known as Mr Tiger. At the time, Mr Tiger’s former home in Hong Kong – which Chan had never visited but always wanted to – was closed to the public. Besides, its fantastical gardens had been demolished in 2004 to make way for luxury housing.

“The one in Singapore, everything remains,” Chan says. “I stayed in this beautiful, quite big garden for a whole day. I remember sleeping on this bench and sucking in all the energy… I was in awe.”

Chan began researching “the garden, the family, the brothers, the whole story of the Tiger Balm legend,” but not everything was available online. Then, in 2019, Haw Par Mansion in Hong Kong reopened, “and luckily, I made an appointment, which was really difficult,” Chan says.

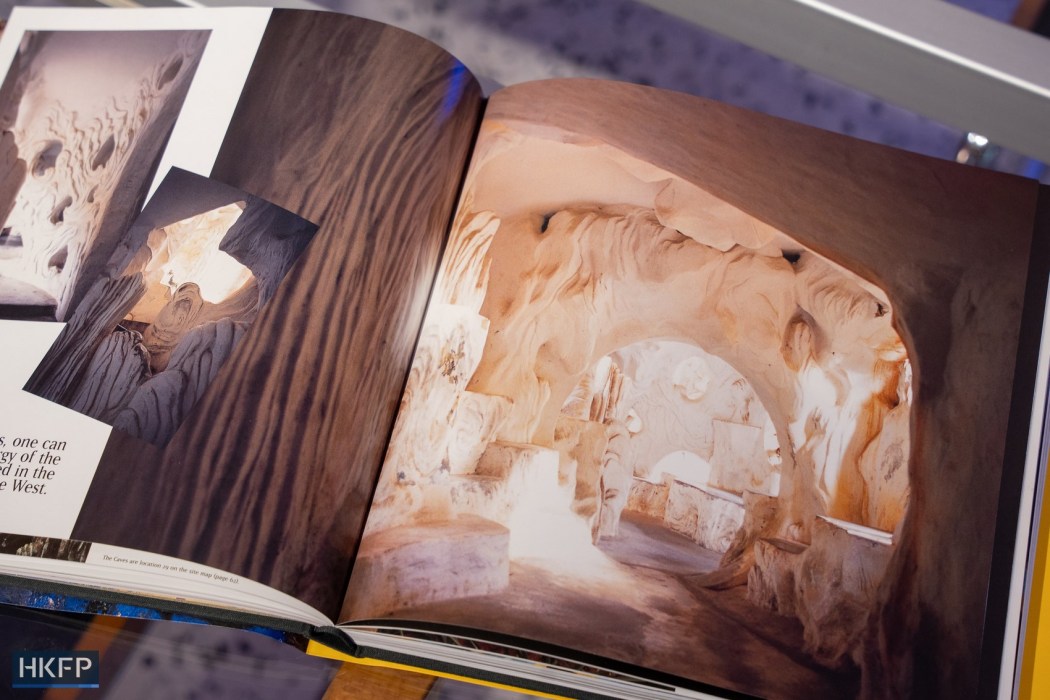

“When I got to the mansion, I was reminded of everything I had seen in Singapore,” she says, adding that she stayed so long that the staff had to ask her to leave. But before she did, she bought a book about the Tiger Balm brothers’ many gardens, which would prove pivotal in both filling the gaps in her knowledge and in her own creative process.

She pored over its hundreds of pages, absorbing the images and information contained within, until one photograph stopped her in her tracks. “And I was like, ‘oh shit they have a cave’.” And even though Chan had never seen Mr Tiger’s cave before, it looked remarkably similar in style and construction to her own.

“And then I looked through [the book] more, and flipped and flipped and flipped,” she says. When she got to the Aw family tree, she said: “I threw the book away. I was like, ‘shit.’ [Mr Tiger] died on the day I was born, and [in] the year my dad was born, too.”

“My dad had just passed away. All these coincidences just added up and this discovery affirmed what I was doing and why I was doing it. I almost felt like I had a mission,” Chan says. “I was meant to build this cave.”

Only then, Chan says, did she know what to do next. “So, I spent another year making the video, the ceramics, making the website, booking system, the four doors – that installation – and putting everything together and thought through the whole setting of the show.”

The cave experience culminates in a very private viewing of that video, in a space that accommodates just three people. It tells the story of the tiger daughter of Haw Par Mansion who is “consumed by darkness,” but is ultimately saved by Tiger Balm and makes her way to the sea, where she finds freedom.

‘You will be good by the sea’

Chan’s cave installation, “She Told Me to Head to the Sea,” got its name from a chance encounter with a “mysterious woman” who walked up to the artist while she was living in New York, grabbed her arm and told her: “‘You have to go to the sea!’ She was like, ‘the sea is good for you, if you’re surrounded by the sea, you will be good by the sea’.”

About a year later, Chan, who studied at Parsons School of Design in New York and started her ceramic sculpture practice there, developed eczema “from head to toe.” It was, she says, “very uncomfortable,” showing a picture of her neck and chin covered in angry red patches.

“I was always touching a lot of chemicals, always touching a lot of dust,” Chan says. And, despite never intending to return to her hometown, “I had no choice but to move back to Hong Kong,” she says, almost whispering: “which is closer to the sea.”

For several months, she was unable to touch ceramics, to create in the way she knew how. “It sucked, yeah, it was really upsetting and depressing, because what you love to do the most kills you, that was how I felt.”

She expected to return to New York after she was cured of her eczema. “And then my dad passed away in 2018. And that part I never expected, because it was so sudden,” Chan says. “I couldn’t [leave] because my dad passed away and I wanted to be with my mom. And so I waited and, as soon as I waited… 2019 started… everything started. And I was still going through grief. I then started to feel fucked.”

Chan moved out of her parents home, she began building the cave and, after several months, she moved into a village house in Sai Kung.

“I was standing in front of the window looking out at the sea in Sai Kung, and I was like: ‘shit, maybe four-five years ago somebody told me I’d be good by the sea’,” she says. “And I’m pretty good, I don’t have eczema, I started running. It’s like when you move to Sai Kung, you start getting better.”

Deep within the cave

“She Told Me to Head to the Sea” is both surprising and surreal, a negative space from which light and logic are absent – to excellent effect. The less known about what lies within, the better.

“I remember walking in [Fong Tak Park] and thinking it could be interesting if the extended version of that outdoor cave comes indoors, and playing with that cave – which is supposed to be underground or tunnelish – lifting it up in a high rise,” Chan says.

You enter Chan’s high-rise cave, eventually, after being presented with four doors and asked to choose your own adventure. The experience is deliberately disarming.

“I liked the idea of having [visitors to the cave] choose [their] own door, because that is also how I felt,” Chan says. “You are opening a door that you chose, without knowing what is behind it.”

Odds are that you will first come face to face with the waterfall. Keep trying, but not after experiencing the sight and sound of the cascade in front of you. This early reference to the water curtain that kept the mouth of the Monkey King’s cave hidden is no accident. Nothing about Chan’s cave is. Her father was born in the year of the monkey in the Chinese zodiac and, she says, “he always gave me an idea of a Monkey King.”

Take the torch that has been left for you and let its beam lead your eyes around the cave, stopping to examine and admire the countless small black forms that occupy the space, which – once your eyes adjust – is illuminated by dimmed Edison bulbs and miniature LEDs that glint as though there are cracks where the light gets in. Strange noises wash through the cave, drawing your attention at times to the objects placed within it.

A bronze bell owned by Chan’s late father stands on a reception desk – attended, bizarrely, by a Furby – inviting you to ring it. The chime penetrates the darkness with its clarity, and guides you through to the next dreamlike chamber, where the screening awaits.

Now that the installation is open to the public, “it’s almost like the story has gone to the next chapter,” Chan says.

“I feel like my healing journey is progressing,” Chan says. “Having the cave by myself is one thing, opening it up to people is another thing. I feel like it gives the cave another life, and it’s the process of transitioning to a different stage, I’m very happy about it and I feel like I’m truly healing, it’s definitely healing me.”

“She Told Me to Head to the Sea” is open Saturdays to Tuesdays through April. Up to three people can visit at a time, and prior booking is necessary.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.