On October 23, Hong Kong’s security chief John Lee officially withdrew the extradition bill from the legislature – but by then it was too late.

What began as opposition to an ill-conceived law had escalated into a citywide pro-democracy movement, with millions taking to the streets over the course of six months.

The bill, which was originally touted as a solution to a “legal loophole,” would have allowed fugitive transfers to jurisdictions such as mainland China. However, it quickly came to mean something different – and altogether more sinister – to the general public.

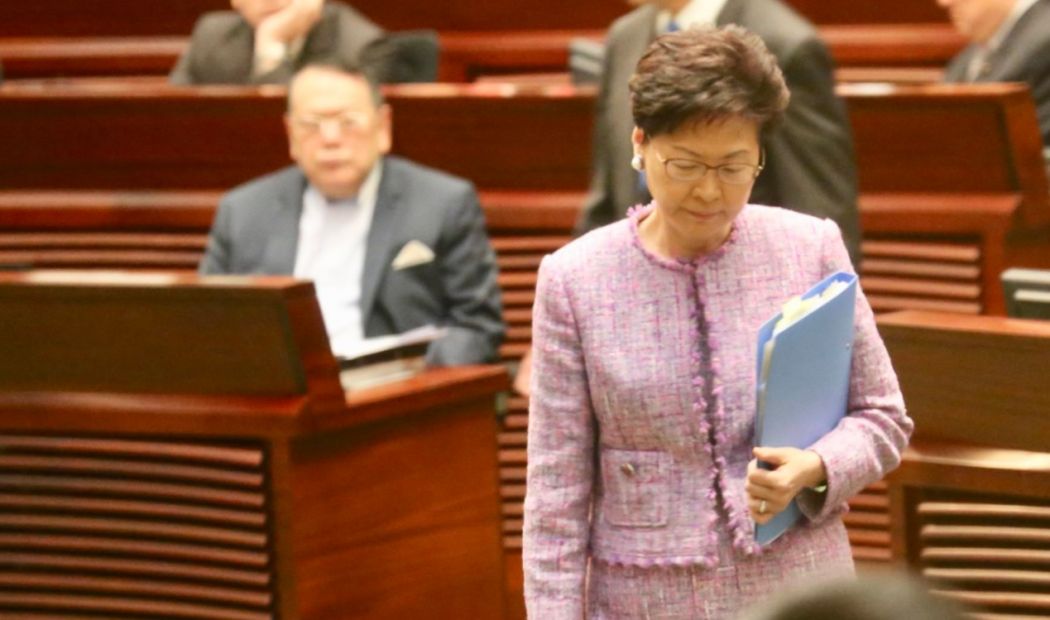

For many, it triggered deep-seated anxieties about an opaque and unfair justice system under Beijing’s rule. Viewed in a local context, it also embodied the worst aspects of the Carrie Lam administration: arrogant, disconnected, and lacking in public accountability.

Lam’s career-defining political misstep also gave rise to an unprecedented coalition, with people across different generations, professions and social classes united in discontent. By the end of July, it had grown into a fully-fledged democratic movement with five “key demands.”

The extradition bill was “suspended” in June, declared “dead” in July, but what the protesters demanded – a complete withdrawal – was only announced by Lam in September. By the time Lee made the withdrawal official at the Legislative Council, it was months overdue and protesters had already raised their asking price.

Despite the delay, the withdrawal of the extradition bill marks the only time that Hong Kong protesters wrested a political concession from the Carrie Lam administration, a rare victory in the face of the hardline stance adopted by the Beijing-backed government.

In retrospect, the extradition bill – formally known as the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019 – sparked the worst social unrest in Hong Kong for half a decade, and altered the trajectory of the city’s relationship with its government and Beijing.

The bill may now be dead, but it will continue to haunt Hong Kong for years to come.

”Timeline of key events“

February 13 – Democrats decry ‘Trojan horse’, says extradition plans may harm city’s judicial protections

February 14 – Plans to update Hong Kong-China extradition law under fire as security chief says no public consultation needed

February 19 – Hong Kong’s new one-off China extradition plan seeks to plug legal loophole, says Chief Exec. Carrie Lam

February 26 – Taiwan rejects Hong Kong govt’s extradition proposal

March 5 – Barristers, scholars and democrats oppose update to Hong Kong extradition law as consultation ends

March 7 – New pushback from business sector and Taiwan politicians against extradition bill

March 31 – 12,000 Hongkongers march in protest against ‘evil’ China extradition law, organisers say

April 28 – 130,000 protest looming China extradition law, organisers say

June 15 – Hong Kong suspends controversial extradition bill after months of protest and criticism

July 9 – Hong Kong’s Carrie Lam declares extradition bill ‘dead’, but stops short of full withdrawal

September 4 – Hong Kong to officially withdraw extradition bill from legislature, but still no independent probe into crisis

October 23 – Hong Kong officially withdraws controversial extradition bill from legislature

How did the bill come to be?

On February 12, the pro-Beijing DAB party brought a grieving woman to meet the press. The woman’s 20-year-old daughter Poon Hiu-wing was killed almost exactly a year ago during a trip to Taiwan.

Poon travelled to Taipei with her boyfriend Chan Tong-kai, but she never returned. Hong Kong police arrested Chan after he fled back to the city, but were unable to charge him with murder in local courts.

The victim’s mother wanted Chan to face justice in Taiwan, but Hong Kong had no extradition arrangement with the self-ruled island. In response, DAB party chair Starry Lee and her colleague Holden Chau proposed amending the city’s laws to make the transfer possible.

For months afterwards, the Hong Kong government would cite Poon’s murder and defend their proposal as a “question of justice” – though it raises the question of why the proposal did not come sooner, as Poon was killed in 2018.

While the DAB appeared to be the originator of the idea of amending the extradition law, most local observers believe that they only hosted the press conference at the behest of the Carrie Lam administration.

What does the bill do?

In short, the amendment bill would have allowed Hong Kong to accept extradition requests from countries where there is no prior agreement. The new system would operate on a “one-off case-based approach,” with the chief executive and local courts playing key roles in determining whether a request is approved.

Prior to the 2019 bill, Hong Kong had two major models for extradition: it has long-term bilateral extradition agreements with 20 countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. It also has a system for handling one-off extradition requests, but such cases must be scrutinised by the Legislative Council.

Neither of those systems applied to Taiwan, mainland China or Macau.

The Security Bureau wrote in February that the existing laws were not applicable to extradition requests “between Hong Kong and other parts of the People’s Republic of China, and therefore the requests arising from the Taiwan homicide case cannot be handled, highlighting the inadequacy and shortcomings of the current regime.”

Despite using Poon’s murder as a pretext for legislation, the Hong Kong government did not limit its proposal to Taiwan – a tricky manoeuvre given that Beijing does not recognise it as an independent state. Instead, the proposed system would apply to all nations where Hong Kong lacks an extradition deal.

Under the plan, the chief executive would have the authority to issue a certificate after receiving an extradition request from a foreign jurisdiction. Local authorities will then bring the certificate to the courts, which will decide behind closed doors whether to grant a provisional arrest warrant.

“On timeliness and confidentiality, this will better suit the actual operational needs,” the Bureau wrote, claiming that human rights safeguards will remain in place. The process would not have any oversight from the legislature.

Why did democrats oppose the bill?

Upon its introduction in February, the bill was immediately criticised by the pro-democracy camp in the Legislative Council. Then-camp convenor Claudia Mo called the bill a “Trojan horse” that may undermine the barrier between the legal systems in Hong Kong and the mainland, which lacks human rights protections.

“It’s obvious that Hong Kong people lack confidence in the mainland Chinese judicial system, and we’re worried that Hongkongers and perhaps dissidents living in Hong Kong could face framed charges,” Mo said at the time.

Mo also opposed the move to enhance the chief executive’s authority: “This is more than unsettling because one person can just decide… and bypass the legislature, and that could easily lead to abuse of power.”

Political group Demosisto spearheaded some of the early protests against the bill, popularising the term sung zung to describe the bill – a pun that meant both “send to China” and “death.”

On March 15, nine Demosisto members were arrested after a sit-in at the lobby of the government headquarters in Admiralty. “Withdraw the extradition law! Oppose legalised kidnapping,” they chanted, before police came to carry them out.

Why did lawyers and human rights groups object?

Early opponents of the bill also included lawyers, journalists, and human rights watchdogs. In March, the Hong Kong Bar Association – the city’s professional body of barristers – accused the government of “jumping the gun” with the proposal and failing to fully consult the public.

The proposal could have “significant and wide-ranging effects” that could undermine Hong Kong’s reputation as a free and safe city with the rule of law, the Bar Association said. It also rejected the government’s line that there was a “loophole” in the law, saying that the lack of an extradition agreement with mainland China was intentional.

The legal subsector of the Election Committee – eligible to vote in the small-circle election that determines the chief executive – added to the chorus about a month later, expressing “deep concern” over the bill in a joint statement.

The Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) said that the change to Hong Kong’s extradition laws could enable China to get hold of journalists in Hong Kong with all kinds of unfounded charges, and bring an end to the limited freedom of speech that Hong Kong still enjoys.

China backs the bill, but Taiwan demurs

From the start, the Taiwan government treated Hong Kong’s extradition bill as a political matter. One of its early objections was that the bill designated Taiwan as part of the People’s Republic of China, which was seen as denigrating to its sovereignty.

The Mainland Affairs Council – an agency under the Executive Yuan that handles cross-strait relations – said in February that it would not accept any rendition agreement as long as the Hong Kong government was operating under the “one-China” principle.

The Council forcefully rebutted the claim that Taiwan came up with the idea of the amendment, saying that it was “utter nonsense,” and later threatened to issue a travel alert for Hong Kong if the bill was passed.

In a direct rebuke to the Hong Kong government, the Council has said multiple times since March that it would not seek to extradite the murder suspect Chan even if the amendment became law – effectively nullifying the justification relied upon by Carrie Lam and her ministers.

Mainland Chinese authorities, on the other hand, remained staunch supporters of the bill. Even in mid-May – after massive street protests saw turnouts of well over 100,000 – Zhang Xiaoming, director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, still described the move as “necessary, appropriate, lawful and reasonable.”

Beijing was less vocal during the early stages, and its relative silence fueled speculation that the idea originated from Lam, instead of her superiors. However, last week, Reuters reported that the impetus for the idea came not from Lam, but from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection – China’s anti-graft agency.

A legal mechanism for extradition would avoid the politically messy process of “kidnapping” fugitive targets just out of Beijing’s reach, such as billionaire businessman Xiao Jianhua who was allegedly abducted by agents from his Hong Kong hotel in 2017. In March, a former Chinese top security official claimed that “more than 300 fugitives” were evading mainland authorities by staying in Hong Kong.

Government slow to concede

From the start, the Hong Kong government sought to reassure the public that the extradition bill would not be political – that the dreaded scenario of dissidents being taken across borders would not happen.

Secretary for Security John Lee went as far as saying that no public consultation was needed for the bill, only backing down later and agreeing to a 20-day consultation period.

“The Taiwan case highlighted a large deficiency in the existing law… we must find a way to solve the loophole in the long-term,” Lee told reporters at the time.

On February 19, Chief Executive Carrie Lam joined Lee in using the “loophole” terminology, which became the dominant government narrative. When asked why the loophole was not plugged during the 20-odd years since the Handover, Lam said that it was because the Taiwan murder case only happened recently.

“The parents of the victim have not stopped writing letters to the government… If we act too carefully, and slowly consult society or issue consultation papers, then I am afraid we will not be able to help with this special case,” she said.

Hints of the bill’s demise came as early as March, when the business sector – long an ally of the establishment – broke ranks and voiced concerns.

The American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (AmCham) said that it had “serious reservations,” which stemmed from the international business community having “grave concerns about the mainland legal and judicial system.”

It was the business community that first managed to extract a concession from the government: on March 26, it excluded nine types of commercial crime from the proposed bill, including those relating to bankruptcy, intellectual property, company law, securities and futures trading.

Few found the concession to be satisfactory, and it opened the government up to a new line of criticism – that it was giving favourable treatment to big business. The AmCham remained unimpressed by the changes, warning that the bill would “reduce the appeal of Hong Kong” to international companies.

Growing local and international backlash

While many recall the citywide protest movement as starting in June, local attempts at mobilisation actually began in March.

Protest turnouts rose dramatically over the space of a month: on March 31, around 12,000 people took to the streets. The number increased ten-fold on April 28, which had organisers put the figure at 130,000.

Meanwhile, foreign bodies such as the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC) sounded alarm bells over the extradition bill, saying that it would “diminish Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe place for US and international business operations.” The USCC comments were soon echoed by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

The government steadfastly refused to budge on the bill, and tried to have pro-Beijing lawmakers rush it through the Legislative Council in May. The ensuing debacle saw opposing factions holding “parallel meetings” over the disputed legitimacy of the process.

When over a million people took to the streets on June 9 – presenting irrefutable proof of public opinion – the fate of the bill was sealed.

Hong Kong Free Press relies on direct reader support. Help safeguard independent journalism and press freedom as we invest more in freelancers, overtime, safety gear & insurance during this summer’s protests. 10 ways to support us.