Beijing’s formal White Paper document only laid down the basic foundations and definitions for the central government’s overhaul of Hong Kong’s postcolonial political order. The White Paper was issued on December 20, a day after Hong Kong’s first “patriots only” Legislative Council election was held under the new rules.

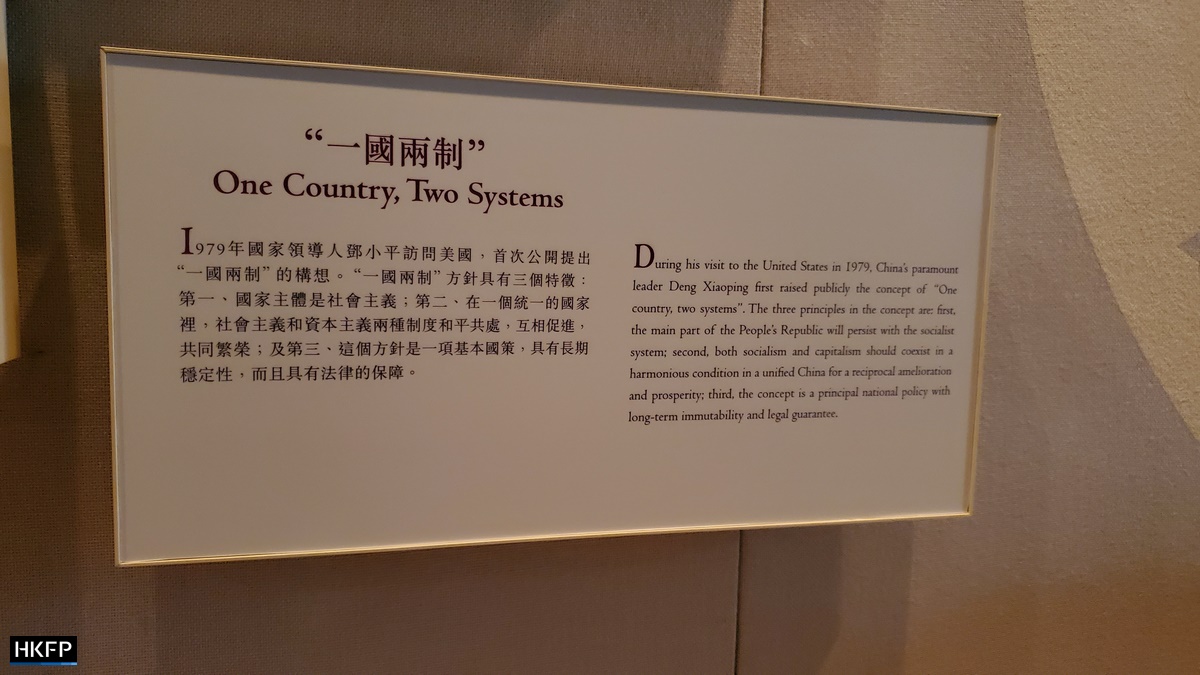

The definitions are meant to be as reassuring as possible under the circumstances – all about continuity with the postcolonial promises and principles for “one country, two systems” remaining intact. The eventual goal is still “universal suffrage elections.”

This suggests that the central government has no immediate plan to transform one country, two systems into a state of fully fledged “one country, one system” integration. It also suggests that Hong Kong’s local Communist Party branch, documented in a book by Christine Loh some years ago, will not be emerging from underground to take its place as the leader of just another provincial Chinee government. Hong Kong is apparently not to be declared a “red” territory any time soon.

But while the words and promises may remain unchanged in name, their meaning in practice bears little resemblance to how they are still being advertised, and what they originally conveyed and were understood to signify.

The new rules used for the December 19 election were designed to exclude all but the most reliable pro-Beijing candidates and to ensure their victory via gerrymandered election districts. These were drawn to favour pro-Beijing residential and voting patterns in the three regions of Hong Kong Island, Kowloon, and the suburban New Territories.

The new election system is, in fact, an adaptation of the current mainland model, transposed for use under Hong Kong’s one country, two systems design. The mix is a variation on the mainland People’s Congress system, which is itself a mix of basic-level direct elections, indirect selection, and consultative appointments – all with strict Communist Party vetting.

Experts and opinion leaders have been doing their best, trying to generate public approval and popular enthusiasm for the way forward. They have a steep mountain to climb.

International public opinion – European and American – is not impressed. “Rigged,” “sham,” “farce,” and “a mockery of democracy” are among the words that have been used to describe Hong Kong’s recent election. Officials here and in Beijing have protested the insults, but so far no one has apologised or issued a retraction.

Hong Kong’s heretofore pro-democracy voting majority has turned a deaf ear as well. And why not? All their most popular politicians have been methodically removed from the political scene: either by disqualification or incarceration. Others have fled to safety overseas.

Those remaining unscathed chose to boycott the election and voters mostly did the same. Turnout on December 19 was only 30 per cent of all registered voters, less than half the rate in Hong Kong’s last election, in November 2019.

Even the newly minted Legislative Councillors seem not to fully appreciate the roles they’ve been assigned to play – as vanguards and exemplars for the second of Beijing’s governing experiments here.

It follows the failure of the first attempt that spanned the better part of 40 years, including the two decades leading up to Hong Kong’s 1997 transfer from British to Chinese rule and the two decades since.

The second system began with the imposition of a national security law in June 2020, and was defined politically by the revamped election system, promulgated by the central government for Hong Kong early last year.

Promoting people’s democracy

The essence of the contradiction between Beijing and the democracy movement in Hong Kong was the dual use of the term, “universal suffrage.”

Hong Kong democrats were campaigning for Western-style democracy and elections, and all that goes with them.

China’s political system also acknowledges the principle of universal suffrage, enshrined in Article 34 of the national constitution. It’s just that China’s elections proceed under the Communist Party’s direction from the central leadership in Beijing, down to the lowermost county-level party secretaries, and the mixed People’s Congress system is the result.

The new rules that Beijing officials are trying their best to promote for Hong Kong are based on mainland principles and practices, and the themes derive from two additional Beijing statements extolling the virtues of China’s governing system.

Unlike the White Paper, these were not timed specifically to justify Beijing’s Hong Kong project, but in response to US President Joe Biden’s mid-December virtual Summit on Democracy.

More than one hundred countries were invited to participate, including Taiwan, but Beijing was not among them. As an added affront, self-exiled Hong Kong activist Nathan Law was included among the speakers. Officials wanted their defiant pushback to be heard loud and clear.

Both documents were dated December 5: China: Democracy That Works, issued by the State Council’s Information Office; and The State of Democracy in the United States, from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The China model is promoted in old-fashioned Communist Party terms with no apologies. China’s constitution describes it as a “socialist country governed by a people’s democratic dictatorship, led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants. The fundamental nature of the state is defined by people’s democratic dictatorship.”

“Democracy and dictatorship appear to be contradictory in terms, but together they ensure the people’s status as masters of the country” – a unified whole dedicated to the wellbeing of all. It is only a “tiny minority” that must be sanctioned but it is in the “interests of the great majority and ‘dictatorship’ serves democracy.”

The disclaimer about a tiny minority remains a constant theme, used to justify repression in the interests of the greater good. Officials used it in the same way when they introduced Hong Kong’s national security law in June 2020.

China’s political system is based on people’s congresses that are appropriate for a people’s democratic dictatorship. This is the best way to guarantee the people’s status as master of the country. This system is also promoted as “whole-process people’s democracy.” It serves to prevent the rise and fall of ruling regimes evident throughout human history.

In contrast, the American form of Western democracy was totally trashed. It had degenerated over the years and deviated from the original ideals. The result is a sick form of democratic rule, based on money, politics, elitism, polarisation, and dysfunction.

China’s form of democratic dictatorship, on the other hand, can boast wide public participation and strong government oversight, and is all around more effective as a governing system.

A unique ‘capitalist democracy’

These official verdicts on mainland Chinese and Western democracy are now being transposed for use in the post-2020 version of Hong Kong’s one country, two systems governing formula. Neither “mainlandised” nor Western, Hong Kong is to have a “new Hong Kong-style capitalist democracy.”

This was the message from Wang Zhenmin, presented at a high-profile promotional event held in Beijing on January 11. Wang heads the national security affairs department at the central government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office in Beijing. He is also director of the Center for Hong Kong and Macao Studies at Tsinghua University.

The occasion was a forum with several sponsors, the most prominent of which was the semi-official Chinese Association for Hong Kong and Macau Studies, a leading promoter of official Beijing views on controversial Hong Kong matters.

Its president is Xu Ze, a former deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office. Another key opinion leader in these matters is Hong Kong professor emeritus Lau Siu-kai, who is vice president of the association.

According to Wang Zhenmin’s melodramatic presentation, Hong Kong would be doomed if its political system could not ensure that patriots would rule Hong Kong. Anti-China forces colluding with foreign forces had been sabotaging Hong Kong’s democratic development by promoting Western-style democracy.

The entry of such forces into the Legislative Council and Election Committee and the possibility of such a person becoming chief executive were all too terrible to contemplate. Both legislative and executive power would be lost. It would lead to the collapse of governance.

If Hong Kong adopted Western style democracy, there would be continual upheavals, and everything would focus on the perpetual election cycles. Social and economic problems would never be solved.

The solution was Hong Kong’s newly revamped political order. Its democracy would not be mainlandised, nor would it be Western style. It would be a new thing, a Hong Kong mix of capitalism and democracy.

Beijing would direct Hong Kong’s democratic development to ensure it remained on the right track. But checks and balances were expected of those in Hong Kong who occupied the seats of power, whether legislative or executive. Well-meaning criticism was necessary.

Xu Ze also spoke at the forum, repeating the same message. Hong Kong had been destined for chaos, he said, without consensus on major political and legal issues. Even among the “social elite” there were biases and misconceptions about what one country, two systems was supposed to mean. And their fallacies became “weapons of thought” for anti-China destabilizers leading to what he called the “colour revolution” protests of 2019.

Beijing’s officials frequently evoked this colour revolution theme in 2019, claiming the protests were aimed at regime change of the kind that emerged in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. It evidently still weighs heavily on the minds of China’s leaders in Beijing.

Xu said that after contemplating Hong Kong’s post-1997 experience, Xi Jinping himself had come to the conclusion that putting patriots in charge of Hong Kong’s government was the only way out, the only way to prevent continuing chaos.

Lau Siu-kai had less to say than others at the January event in Beijing, but he knows the subject well. In fact, he even wrote a book about it and could claim the ideas about Hong Kong’s possible collapse and redemption as his own.

Lau’s work, published in 2014, in Chinese, was titled Hong Kong’s Unique Path of Democratization. In it he argued that while Hong Kong had what are now thought to be the necessary conditions for democratic development, its path to democracy would have to be unique due to political realities. His conclusion was that “the Western democratic model is absolutely not suitable for Hong Kong” and cited several reasons.

First, Hong Kong is not independent and can never be. Hong Kong is part of China and does not have the right to dictate the terms of its own political system.

The British, external foreign forces, Hong Kong’s pro-democracy opposition, and Hong Kong residents who agitated for the Western democratic model, all see Hong Kong, in effect, as an independent entity. They reject Hong Kong’s responsibility to safeguard national security and have even blocked passage of such legislation.

Lau also cites Beijing’s long-standing lament about such people aspiring to establish a Western-style democracy in Hong Kong so that it can be turned into a pro-Western base of subversion against China.

In its original form, this lament – dating from the Communist Party’s 1949 Civil War victory – didn’t include democracy in Hong Kong but only Hong Kong’s use as a base of subversion to destabilize the new communist government.

Secondly, Western-style democracy is “procedural democracy.” As long as an election is fairly conducted, the results are regarded as representing the will of the people and must be respected regardless of the consequences.

In Beijing’s view, Hong Kong’s one country, two systems design is a major national policy and a strategic goal that must be faithfully implemented whether the people like it or not. Compared to such goals – national unity, national security, stability, good governance – democratisation is “much less important.”

The political system is just a “tool,” a means to an end, not the end in itself. So, if one tool doesn’t work then it must be “re-tooled,” which is what Beijing has just done to Hong Kong’s post-1997 system.

Finally, to achieve all this, Hong Kong must be ruled by patriots, people who accept the post-1997 system as Beijing evidently always intended it to be – but never explained in so many words.

Meanwhile, the vetting of candidates had been a haphazard affair. A “substantial proportion of Hong Kong residents and politicians harbour anti-China and anti-communist opinions.” Yet the vetting system allowed such people‘s representatives to enter the governing system where they played the role of a “disloyal opposition.”

Consequently, the one country, two systems design had failed to function as it should. Concluded Lau, Hong Kong’s flawed political system was the root cause of the post-1997 political impasse.

Specifically, the turmoil of the past decade and the 2019 colour revolution forced Beijing’s hand and compelled the drastic overhaul of Hong Kong’s political system. It is now a tool well-suited to the end goals.

Over time, if all goes well, the new tool can be revised to allow more participation by “Hong Kong residents and former oppositionists” who are willing to pursue their political careers within the new constitutional order.

Nor was this Lau’s last word on the subject. In a follow-up piece, published in China Daily on January 18, he elaborated on a more sinister theme, devoted to the aim of removing all anti-China forces not just from the political realm but from all of society.

“In order to ensure the long-term success of the new electoral system, Beijing and the HKSAR government have worked together to oust the ‘anti-communist,’ ‘anti-China’ and other subversive elements from the Hong Kong society.”

Correction 31/1: A previous version of this opinion piece incorrected stated that Lau Siu-kai did not speak in Beijing in January.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.