By Holmes Chan

Hong Kong has emerged a more unequal city, its freedoms curtailed and international shine dulled after five years with Carrie Lam at the helm, analysts say, as her turbulent leadership draws to an end.

Lam, Hong Kong’s first woman leader, took office promising to heal divisions and tackle livelihood issues, especially a housing crisis.

Her term was instead dominated by massive democracy protests and Beijing’s subsequent crackdown, as well as a zero-Covid pandemic strategy that kept the city isolated while rivals reopened.

She is on track to depart at the end of June with the lowest approval ratings of any leader since the handover from Britain.

In her final policy address last October, Lam described Hong Kong as “much stronger than ever” after China intervened to ensure stability.

Her government survived the mass protest movement, but many say she failed to deliver on life improvement pledges — which even China’s leadership says are at the heart of the city’s “deep-rooted social conflicts.”

Last year, 1.65 million Hong Kongers — nearly one in four — were living below the government’s official poverty line, which for a one-person household means HK$4,400 ($560) a month.

This was the highest level since records began 12 years ago.

“The grassroots have been very neglected,” said Sze Lai-shan, deputy director of the Society for Community Organization.

“Sometimes it feels like (the government) is living on a different planet.”

Even pro-establishment figures have been unimpressed.

“You may say (Lam) has been working very hard, but little has been achieved in solving the deteriorating livelihood issues and Hong Kong’s deep-rooted conflicts,” senior Beijing advisor Lau Siu-kai told AFP.

World’s most expensive property

Last July, China’s top official on Hong Kong affairs Xia Baolong gave a speech widely seen as a reflection of Beijing’s growing impatience with the housing crisis, something every leader since the 1997 handover has failed to solve.

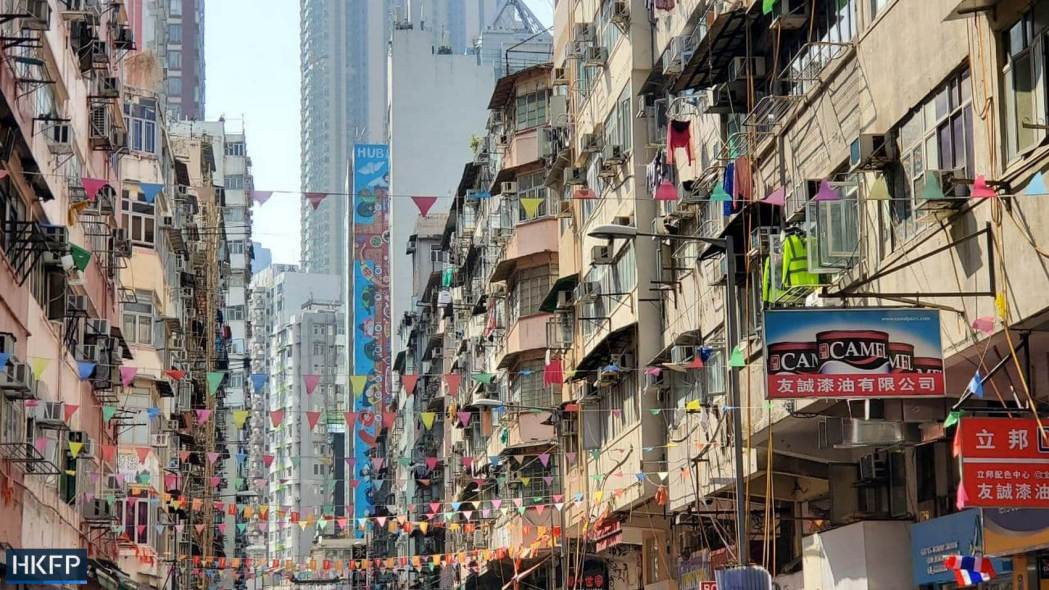

The city, Xia said, must “say goodbye” to cage homes and the tiny shared apartment rooms where some 220,000 Hong Kongers still dwell.

Hong Kong has long held the title of the world’s most unaffordable housing market, where a study this year showed the median property price is 23 times the median household income.

Lam increased public housing supply, more than her predecessors, but demand still outstripped supply with the wait time increasing to six years.

Chan Kim-ching, a land-use researcher at the Liber Research Community, said Lam overly prioritised building flats to buy.

“By putting home ownership as the goal, it exacerbated the wealth inequality in society,” Chan told AFP.

“(Lam’s) policies do not target those in the greatest need. There is a mismatch.”

Exodus

The last two years of Lam’s term also witnessed a historic outflow of people — fleeing either the political crackdown or some of the world’s strictest pandemic controls.

The departures surged further this year when Hong Kong’s zero-Covid policy collapsed as the more transmissible Omicron variant broke through, killing more than 9,000 people, mostly under-vaccinated elderly.

A net 160,000 people departed Hong Kong in the first three months of the year.

Lam recently acknowledged that the curbs had caused a brain drain among foreign businesses, saying it was an “undeniable fact”.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s ongoing efforts to reshape Hong Kong’s political landscape sparked another emigration wave among locals.

After the 2019 protests were crushed, China imposed a sweeping national security law that criminalised dissent and transformed the once outspoken city.

Police arrested 182 people under the security law. Most of the city’s prominent democracy activists are either in jail or have fled overseas.

In the annual international press freedom chart released this week by Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong plummeted from 80th to 148th place.

Frances Hui, an activist granted asylum in the United States, described Lam as an “obedient enforcer” of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s agenda.

“She accelerated the suppression of freedoms,” Hui told AFP.

The Hong Kong diaspora is steadily growing in places like Britain, Canada and the United States.

“I didn’t expect that taking part in activism will lead to me having to seek asylum,” Hui said.

“That’s a reflection of how far Hong Kong has fallen.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.