When Tung Chee-hwa met reporters from local and international media on July 2, 1997 – the day after being sworn in as the first chief executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region – he was asked what the Handover of the former British colony to China meant for Filipino domestic workers in the city.

“The Filipino domestic help is very much part of our community and I hope they will be here for a long, long time to come,” Tung responded.

One of the more than 150,000 Filipino migrant domestic workers in the city in 1997, activist Eman Villanueva, recalled “feelings of uncertainty” preceding that historical moment. “There was a lot of talk about possible changes after the Handover,” he told HKFP.

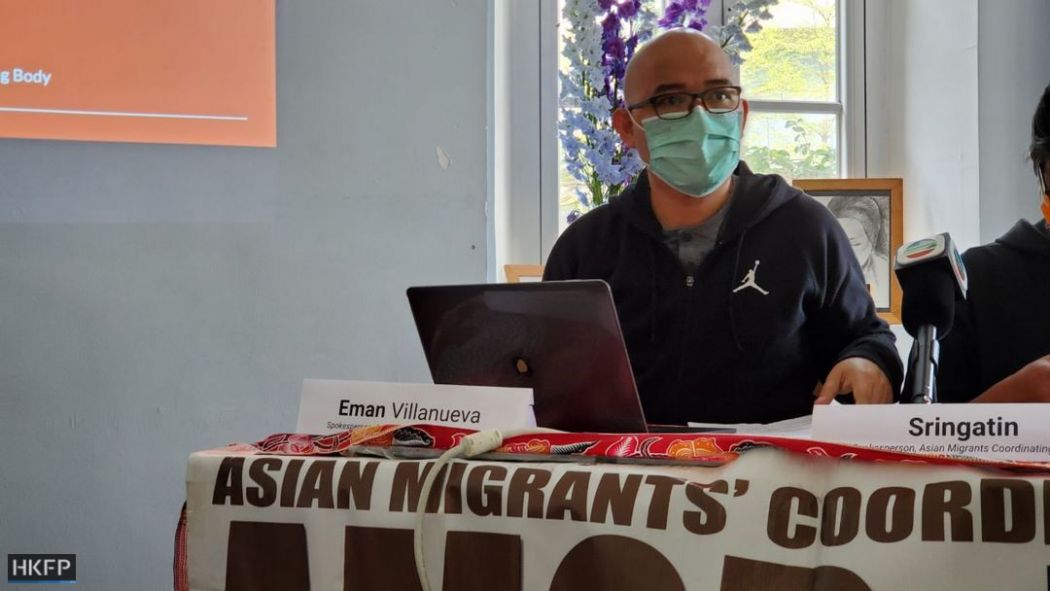

“But as it turned out… in the context of migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, there was really not much change after that,” said Villanueva, who arrived in the city in 1991 and is the spokesperson of the Asian Migrants’ Coordinating Body (AMCB), a coalition of migrant worker groups and unions.

“Most of the problems we faced post-1997 were already there.”

Many of those issues remain in 2022. And without a vibrant activist movement, migrant domestic workers’ rights in Hong Kong might have slid into reverse.

Pre-handover policies

“The two-week rule, for example, it’s been there since the 80s,” Villaneuva said, referring to a policy introduced in 1987 that requires migrant domestic workers to find a new job within 14 days of their employment contract ending or being terminated, or leave the city.

Responding to an enquiry from HKFP, a spokesperson for the Labour Department described the two-week rule as “necessary for maintaining effective immigration control and helps prevent FDHs [foreign domestic helpers] from job-hopping frequently and working illegally… after premature contract termination.” However, it’s “main purpose,” the department said, was “to allow sufficient time for FDHs to prepare for their departure.”

Also unchanged since before the Handover is a law barring migrant domestic workers from the right of abode in the city. “The only difference,” Villaneuva said, between then and now, was a 2013 Court of Final Appeal ruling, which made it “a more definite legal decision.”

In March that year Hong Kong’s highest court sided with the government to overturn a High Court judgement from 2011 that described the law excluding migrant domestic workers from residency as “unconstitutional,” essentially ending years of campaigning on the matter.

The “live-in rule,” which mandates that migrant domestic workers reside with their employers, has always existed, but it has become a more stringent requirement. In a 2003 Legislative Council (LegCo) document, then-chief secretary Donald Tsang laid out his recommendations to “improve the existing mechanism for admitting FDHs [foreign domestic helpers] and to prevent exploitation of the migrant workers,” among them strict enforcement of the live-in policy.

The Labour Department’s spokesperson said that the live-in rule “underpins the long-established Government policy that priority in employment should be given to the local workforce… It is along this policy objective that live-in FDHs have been imported since the 1970s to meet the shortage of local live-in domestic helpers.”

Allowing migrant domestic workers to live out from their employers would be “contrary” to that policy and “would directly expose local domestic helpers to the competition of FDHs,” the department said, adding that the requirement was laid out in migrant domestic workers’ standard employment contracts (SEC). “In other words, FDHs are fully aware of the ‘live-in requirement’ before signing the SEC and that they are admitted to Hong Kong on such basis.”

According to Villaneuva, however, the requirement does nothing to prevent exploitation as Tsang suggested, rather “the live-in rule is actually a policy that promotes modern-day slavery.” Despite decades of organising against the policy, it was upheld by the Court of Final Appeal in 2020.

Junko Asano, a PhD candidate at Oxford researching migrant workers, told HKFP that in spite of “the incredible advocacy of migrant domestic worker unions, labour associations and NGOs since the 1980s, migrant domestic worker rights have remained stagnant because the Hong Kong government relies on cheap labour of migrant domestic workers to reduce the burden of care work on local women and to enable them to enter the workforce.”

Small victories

“Although the migrant domestic worker movement has struggled to fundamentally change the foreign domestic helper scheme in Hong Kong, it has been successful in preventing the backsliding of migrant domestic workers’ existing rights,” Asano said.

In the aforementioned 2003 LegCo document, Tsang endorsed a HK$400 levy “for the employment of FDHs” to be paid by their employers, and a HK$400 pay cut for migrant domestic workers’ minimum monthly wage of HK$3,670 to take effect on April 1, 2003. The pay cut would “reflect downward adjustments in various economic indices,” Tsang wrote.

“The amount of the levy was exactly the same amount as the HK$400 monthly pay cut. So we say that it’s actually the domestic workers who subsidise the employers with their levy,” Villaneuva said.

The proposals sparked mass protests, with several thousand migrant domestic workers taking to the streets over several weekends, but to no avail. In late February, Tsang announced that the government would proceed with both the levy and the wage cut.

It was at this moment that the AMCB decided to shift its focus, Villanueva said. “We decided we should no longer be on the defensive side. We had been under attack for so long, we should now be on the offensive side. And so we shifted the campaign to ‘wage increase now’.”

From 2005 to 2008, and from 2011 to 2019, migrant domestic workers’ minimum monthly salary increased incrementally. “Of course, it took us several years to recover the HK$400 lost,” Villanueva said.

For Eni Lestari, the founder of the Association of Indonesian Migrant Workers in Hong Kong (AKTI-HK) and chairperson of the International Migrants Alliance, this was a successful shift. “The wage has gradually increased,” Lestari told HKFP on the phone from her family home in Indonesia, which she was visiting for the first time in three years.

Lestari discovered activism after leaving her first employer in Hong Kong, in 2000. “I was underpaid… no day off, I was maltreated… I did not have a phone,” she said. She negotiated one day off a month in exchange for a HK$100 pay cut to her monthly salary of HK$1,800 – significantly below the minimum monthly wage of HK$3,670 – and after seven months ran away to the Mission for Migrant Workers.

“That’s when I learned about rights, empowerment, organising – from other nationalities. That’s how I became an activist myself,” she said. She founded AKTI-HK in October 2000 and set about campaigning against the systemic underpayment of Indonesian domestic workers and the high agency fees they faced.

“For Indonesians, since 2000, our focus has been on empowerment, awareness, empowerment, awareness,” Lestari said.

“But of course there were other campaigns with AMCB. We were fighting against the two-week rule, the live-in policy, long working hours, and then physical abuse, and different types of abuse. Even [though] we have our own problems, we have common problems.”

As one of five migrant domestic workers who challenged the HK$400 levy in the courts, Lestari was integral to fighting against what she has called a “discriminatory tax” on migrant domestic workers. Despite losing their appeal, the levy was suspended in 2008 and scrapped in 2013. Lestari considers its withdrawal “one of the big achievements” of the migrant movement in Hong Kong.

From crisis breeds change

Other milestone moments in the movement emerged from moments of crisis. Sringatin, the chairperson of the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union, pointed to the case involving Erwiana Sulistyaningsih, who was abused at the hands of her Hong Kong employer, Law Wan-tung.

The case made international headlines when images of a bruised and battered Sulistyaningsih emerged in 2014. Law was given a six-year sentence after depriving Sulistyaningsih of food, forcing her to sleep on the floor, burning her with an iron and beating her with mops, a ruler and a clothes hanger, leaving her scarred for life.

Sulistyaningsih went on to become the face of a movement advocating reform for Hong Kong’s migrant domestic workers, and – Sringatin, Lestari and Villanueva agreed – waking Hongkongers up to their exploitation.

“Until Erwiana’s case happened, and it became public, there was really no more debate about modern-day slavery happening in Hong Kong,” Villanueva said.

“When there is a big case, public opinion changes,” Sringatin said. “But it really depends on us [to keep the momentum going]. How we deliver the message, how we can make them understand what we are doing in Hong Kong and our situation,” said Sringatin, who came to Hong Kong from Indonesia in 2002 and like Lestari was a victim of injustice.

Even the way people address migrant domestic workers carries meaning, Sringatin said. “I think this can really change the perspective,” she said, adding that the term “helper” – which is still used by the government and many employers in the city – makes it seem “like you don’t have any skills, you don’t have value because you just help.”

“‘Domestic worker’… it’s [about] respect, and [acknowledging that] you have rights as a worker… so this is very important to educate the public.”

Continuing amid civil society crackdown

Since Beijing implemented national security legislation in Hong Kong in June 2020, at least 57 civil society organisations – including unions, churches, media groups, and political parties – have disbanded, including several that aligned with the migrant movement.

Recalling his early days with United Filipinos in Hong Kong in the early 1990s, Villanueva said: “Every time there was a campaign or a protest… we would go to the office of the HKCTU [Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions] and they would allow us to use the rooftop of their office in Yau Ma Tei, and that is where we would make our placards, our banners.”

And even as the migrant movement became more established, “we continued to have that solidarity. They were always in support of our campaigns.” However, “there were also struggles,” Villaneuva added, saying that some members were caught in an “identity crisis” – as unionists and as employers of migrant domestic workers. But “the leadership of the unions were very supportive.”

The solidarity went both ways, with migrant domestic workers supporting the Union of Hong Kong Dockers during their 40-day strike in 2003. “When they held several weeks of strikes, migrant workers were there to Kwai Chung, in the port area, and we delivered food, water, drinks to those who were striking,” Villanueva said.

“Some of the workers were crying because we were apologising, saying we can only give you this, we don’t have much money, but at least we want to stand in solidarity with you.”

Villaneuva said that support “continued until very recently.”

“Those who were very supportive of the migrant cause, we’ve lost many of them in the legislature, and then of course, some of the groups that used to express solidarity with the migrant workers, they no longer exist,” he said.

It has affected activists’ ability to lobby the Hong Kong government, Villanueva said. “It’s more difficult now.”

Sringatin echoed him, calling engagement with the government “very formal.” “We just send a letter, a petition. [To have] dialogue is a little bit difficult.”

Lestari is more explicit. “The Labour Department doesn’t entertain any requests. It will invite us only once a year, during the MAW [monthly allowable wage] review, and that’s all. Either they don’t respond or they use Covid as an excuse. They have closed the door,” she said.

The Labour Department spokesperson told HKFP that “The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government attaches great importance to safeguarding the rights of foreign domestic helpers… in Hong Kong and maintaining Hong Kong as an attractive place for them to work,” adding that “FDHs enjoy equal protection and entitlements as local workers.”

‘Stopping is not really an option’

Villanueva acknowledged that the Covid-19 pandemic had impacted both lobbying efforts and the ability to stage protest actions.

“We don’t know if after Covid, once we go back to the streets and much more active engagement with the government, we really don’t know how it will look,” he said. However, Asano said that she expected the movement to continue. “I doubt that migrant domestic workers’ organising efforts going forward would be significantly impacted,” she said. “

“Even though it’s now challenging to gather in big groups, migrant domestic worker activists can still meet in small groups and relay their concerns to the government through press conferences, dialogues, petitions and other means.”

Regardless of how the movement looks in months or years to come, Villanueva, Lestari and Sringatin – as well as countless migrant domestic workers and activists in Hong Kong – will continue to fight for their rights and their welfare. “That’s the only way to do social transformation,” Lestari said. “If we want to change… we have to rely on ourselves and find ways to change things from the ground up.”

“In Hong Kong, we’re just strangers,” Sringatin said. “We need friends who can support us.”

Villanueva said he believed that there was significant public support for migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, “and I think the proof of that was during the fifth wave of Covid.”

After stories emerged of Covid-positive migrant domestic workers being denied treatment and being forced to sleep on the streets – stories that echo those told during the SARS outbreak in 2003 – migrant workers groups launched an emergency response appeal.

“We were so overwhelmed with the outpouring of support,” Villanueva said, clearly emotional. “Our combined fundraising was able to reach probably more than HK$2 million. That’s why I can confidently say that there are many people in Hong Kong who are supportive of migrant workers. And because of that, we don’t lose hope.”

He added: “The issues we had before, they are the same – if not more – than we are facing now. We just have to continue. Stopping is really not an option.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.