The sedition law, one of Hong Kong’s legacies from the British colonial government, was unused for over half a century until its revival in the aftermath of the 2019 extradition bill protests and unrest.

Along with the Beijing-imposed national security law, it is increasingly used against purported security threats, although some critics see it as a deterrent to free speech and to legitimate criticism of the administration.

HKFP takes a look at the sedition law and how it may shape plans for Hong Kong’s own security law, which the administration has pledged to draft to fill perceived gaps.

Sedition vs National Security Law

The sedition law outlaws incitement to violence, to disaffection and to other offences against the administration while the national security law, enacted in June 2020, criminalises subversion, secession, collusion with foreign powers, and terrorist acts.

While the sedition legislation falls under the Crimes Ordinance, part of the regular criminal law, elements of the national security law can be found in sedition cases.

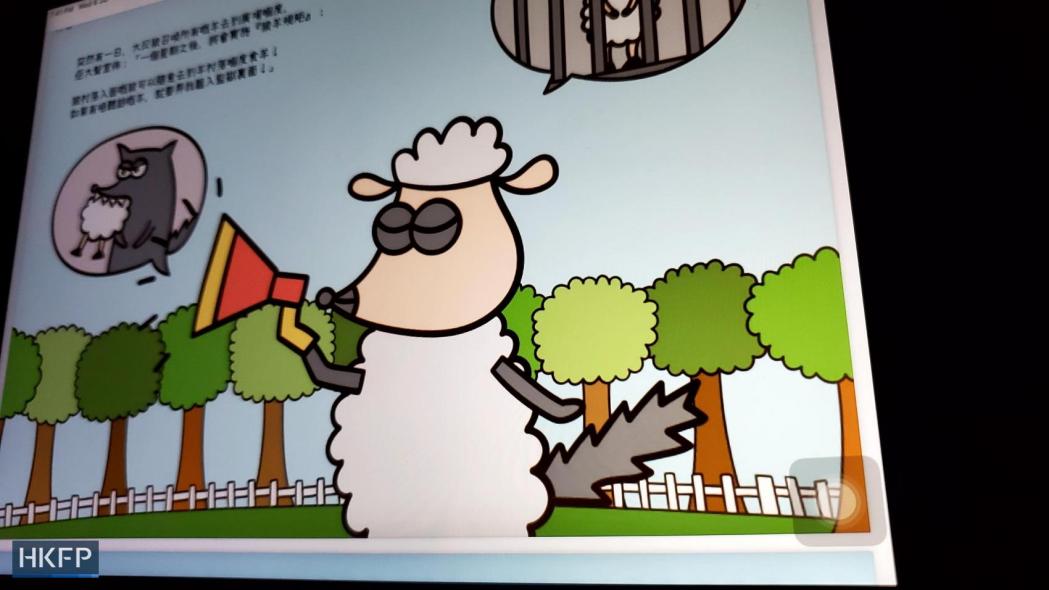

Following an appeal by a former speech therapist accused of publishing “seditious” children’s books, the Court of Final Appeal ruled last December that the stricter standard for granting bail under the national security law also applies to other cases such as sedition, which are seen as security-related.

Both sedition and national security law cases are handled by judges who have been handpicked to hear such cases. National security law defendants are refused the right of trial by jury and appear before a panel of three High Court judges. No sedition cases have been tried at the High Court yet, so it is unclear if defendants will have the right to a jury.

The sedition legislation had been dormant for over 50 years until March 2020, when pro-democracy district councillor Cheng Lai-king was arrested for allegedly acting with seditious intent, after she shared a social media post containing information on a police officer and the officer’s family.

While Cheng was eventually prosecuted over contempt of court, Hong Kong has seen an increase in prosecutions under the sedition law following the arrival of the national security law.

Charges have been brought against not only activists, but also news outlets. Journalists at Apple Daily, the city’s defunct pro-democracy tabloid, became the first media workers to be accused of sedition.

Two days after Apple Daily journalists faced an additional sedition charge, two top editors of Stand News, an online media outlet with a pro-democracy slant, were accused of conspiring to publish seditious publications after the newsroom was raided by national security police.

What can the sedition law tell us about Article 23?

Article 23 of the Basic Law, the city’s post-Handover constitution, requires Hong Kong to pass its own national security legislation.

”The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organisations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organisations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organisations or bodies.“

The first attempt in 2003 to pass such a law sparked a massive street protest that led to the resignation of the then-secretary for security Regina Ip. Successive governments have shelved the issue but Chief Executive John Lee said during his election campaign that Article 23 was a “priority.” However, his administration has yet to set out a clear timeline or proposal for the legislation.

Questions remain on the scope of such a new law given the sweeping nature of the existing national security legislation and the sedition law.

Similar to bail conditions in sedition cases, Secretary for Justice Paul Lam has said that the stricter standard should also be applied to the Article 23 legislation.

Back in 2003, sedition was defined under the proposed Article 23 law as inciting others to commit treason, subversion, secession, or engage in “violent public disorder that would seriously endanger the stability of the People’s Republic of China.”

The offence would have been punishable by up to life imprisonment rather than the two years under the colonial-era law for a first offence.

Sedition during the colonial era

The sedition law originated in the Seditious Publications Ordinance of 1914, which regulated newspapers, books, and other printed materials. The 1938 Sedition Ordinance saw its expansion to include acts and words.

While a statutory defence was provided in the 1938 legislation for reasons such as pointing out “errors or defects” in the administration, the British colonial government used the ordinance, along with the Control of Publication Consolidation Ordinance, to prosecute the pro-China press on at least two occasions in the 1950s and 60s.

Ta Kung Pao’s publication was suspended for 12 days after the newspaper reprinted an article by the People’s Daily following the March First Incident in 1952.

A confrontation between members of the public and police broke out after the colonial government rejected a visit by a comfort mission from Guangdong, following a fire in Tung Tao Village which destroyed thousands of homes.

The People’s Daily article protested against the arrest of demonstrators, as well as the actions of the Hong Kong government. The publisher and editor of Ta Kung Pao were arrested and convicted under the Sedition Ordinance.

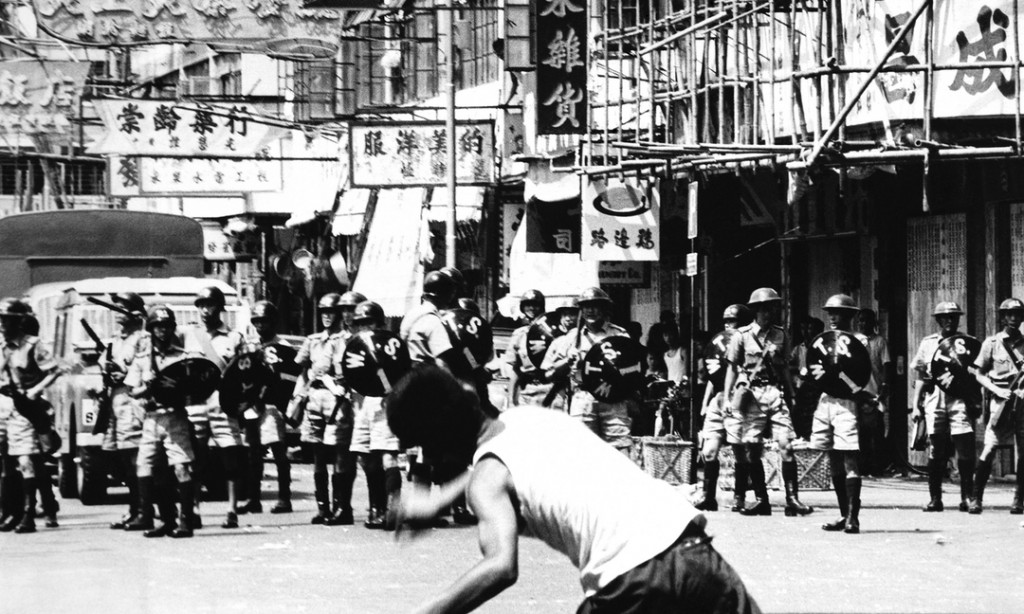

Following the 1967 riots, the Hong Kong government used the ordinances to once again prosecute local pro-China newspapers.

Hong Kong Evening News, Tin Fung Daily, and Afternoon News were charged with publishing false and seditious news, or reports that would incite discontent towards the police. The prosecutions were brought under the Control of Publication Consolidation Ordinance and the Sedition Ordinance.

The three publications were suspended for six months, and their printers and proprietors were jailed for three years.

Protestors were also jailed by the colonial government using the sedition legislation. Among them was former secretary for home affairs Tsang Tak-sing, who was convicted and handed a two-year jail sentence after he distributed anti-government leaflets at his school.

The Sedition Ordinance saw its last major amendment in 1970 to cover incitement to violence and counselling disobedience to the law or to any lawful order. The ordinance was incorporated in the Crimes Ordinance a year later, and incitement to disaffection and mutiny was added to the offence.

Repealing the legislation

Britain repealed the offence of seditious libel in 2009, after the Coroners and Justice Bill was passed. Lord Lester of Herne Hill said in the House of Lords debate at the time that the law was “an archaic and outdated offence that unduly restricts free speech.”

“There is one further important reason for repealing these offences. Across Europe and the Commonwealth, similar offences exist and are used to suppress political criticism and dissent,” he said.

There was also discussion in Hong Kong during the years leading up to the Handover on whether the sedition legislation should be repealed.

In the year approaching the handover on July 1, 1997, the Hong Kong government tabled a bill in an attempt to fulfil the requirements of Article 23 of the Basic Law.

The Patten administration attempted to amend the Crimes Ordinance to include secession and subversion – rather than leaving the issue for the post-colonial government to legislate – but the proposal was voted down by the Legislative Council.

During the discussion in the Bills Committee, then-lawmaker Emily Lau proposed to remove the sedition offence from the Crimes Ordinance. Her suggestion was supported by fellow legislators Margaret Ng, Christine Loh, and Elizabeth Wong.

“Mr Chairman, as I pointed out during the Second Reading a moment ago, the offence of ‘sedition’ is an outdated and serious offence which was made to enhance colonial rule. When the colonial rule is about to end, it is the most appropriate time to delete this offence,” said Lau at a LegCo meeting a week before the handover.

But the motion was voted down in the legislature, as it was opposed by the Democratic Party and the Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood.

The Democratic Party instead proposed amendments “in view of the political reality that the future legislature of HKSAR would very likely legislate on that offence in accordance with Article 23,” to incorporate the Johannesburg Principles for “better protection of human rights,” and to make prosecution more difficult.

While amendments to introduce limitations were passed in the legislature, they were never implemented by the Hong Kong government after the Handover.

This month, 25 years later, the topic of repealing the sedition law emerged again. The United Nations Human Rights Committee urged the Hong Kong government in a report to abolish the colonial legislation, as well as the Beijing-imposed national security law.

The committee also said the government should “immediately stop applying the National Security Law and the Implementation Rules to sedition cases,” and “review pending sedition cases to ensure no one is prosecuted or targeted for the legitimate exercise of his/her right to freedom of expression.”

In a lengthy response to the UN’s “unfair criticisms,” the Hong Kong government said the committee should have paid attention to the “‘soft resistance’ acts, hate speeches and publications which have radicalised the general public since 2019.”

“It should be reiterated that the [sedition] offence is not meant to silence expression of any opinion that is only genuine criticisms against the Government based on objective facts, with relevant defence clearly stipulated under the Crimes Ordinance…,” the statement read.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team