The Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) has raised concerns that the city’s new national security law could have “far-reaching implications” for the press, as it urged the government to provide protection for reporters.

In a proposal shared on Saturday, the HKJA called on authorities to provide clearer definitions for provisions relating to offences, including external interference and theft of state secrets.

What constitutes “state secrets” is too broad, the group said. Journalists receive leaks from government sources from time to time, for example in relation to personnel changes and policy announcements, and it is difficult for the press to determine if the sources are disclosing this information with lawful authority.

Regarding the external interference offence, the HKJA said it was worried that the definition of "foreign forces" was also too vague. The group raised questions about whether attending events funded by overseas business chambers or organisations with foreign links could constitute "collaboration with an external force."

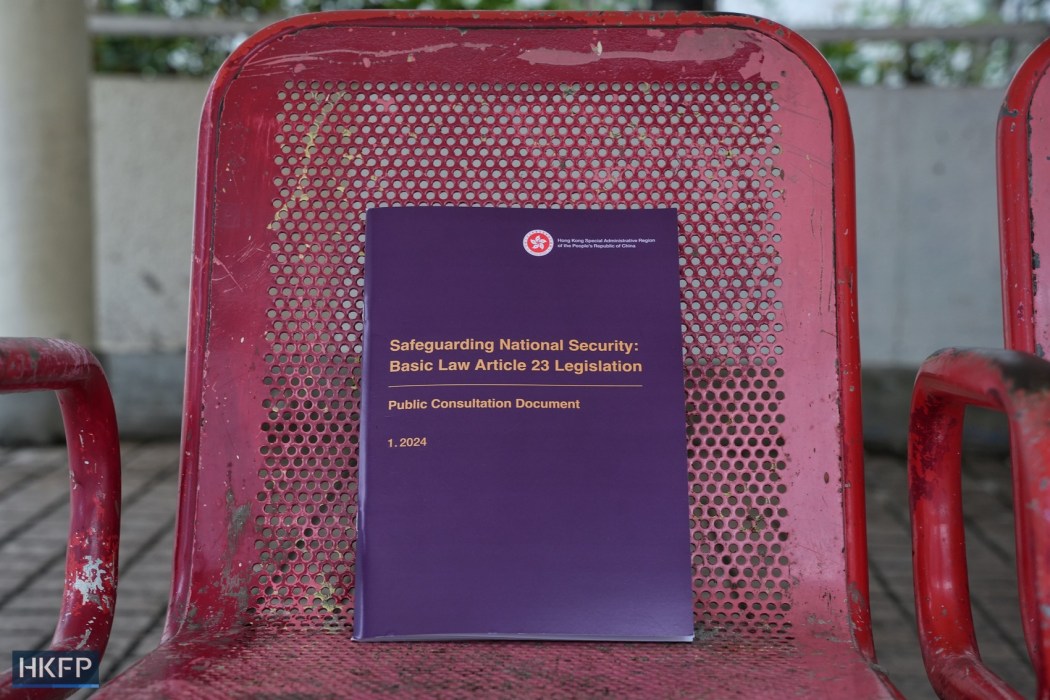

Hong Kong is expected to pass a new national security law within this year per Article 23 of the Basic Law, which states that Hong Kong must enact its own laws to criminalise acts that endanger national security. Colloquially known as Article 23, the homegrown law is separate from the Beijing-imposed national security legislation, which was enacted in 2020 following the 2019 protests and unrest.

The HKJA's submission, made to the Security Bureau, came as the month-long public consultation for the security law draws to a close. Authorities published a 110-page paper on the legislation at the end of January and invited residents and groups to share their views. Chief Executive John Lee has claimed most people support the law.

According to the paper, the homegrown legislation is set to cover five types of crime: treason, insurrection, theft of state secrets and espionage, sabotage endangering national security, and external interference.

In its submission, the HKJA said the press seeks to serve the public interest and hold authorities accountable, and was not a threat to national security. It said that, among the 105 journalists who took part in the group's survey, 90 per cent believed it would have a significant negative impact on press freedom.

"[HKJA] thinks that when enacting the law, the government should avoid [situations where] journalists find themselves caught up in legal trouble due to their regular news gathering, reporting or commentary work," the group's submission, in Chinese, read.

The Hong Kong Federation of Journalists, a pro-establishment group, claimed in response to HKJA's submission that the group did not represent the news industry.

"The HKJA... seriously twisted the facts and attempted to cause confusion and create panic," the group wrote. "They completely fail to represent the views of Hong Kong's media industry."

The HKJA is the largest, and oldest, press group in the city, having been established in 1968.

Rare statement of concern

The HKJA's submission is a rare local expression of concern about the potential impact of Article 23. While overseas activist groups, led by UK-based organisation Hong Kong Watch, have issued a joint statement condemning the security law, opposition in the city has been muted.

In 2003, the last time Hong Kong attempted to legislate Article 23, an estimated 500,000 protesters marched to oppose the law. With the Beijing-imposed national security law in place, under which dozens of civil society groups have collapsed and activists arrested, mass protests have effectively been barred.

In its submission, the HKJA also recommended that, under the domestic security law, there should be a need to prove that there was "material damage" done to national security.

"The association believes that many offenses are currently defined too broadly, which may result in many cases being prosecuted where there is no real risk or very little risk to national security... causing the severity of charges to far exceed the actual harm of the offenses," the group wrote.

The HKJA added that the courts should also have to prove that a defendant intended to endanger national security, in order to be convicted.

"If the prosecution is not able to prove that the journalist had the intention to endanger national security, he or she should not be charged. This can help to protect press freedom," the group said.

The public consultation period will end on Wednesday.

Chief Executive John Lee said last Tuesday that the “majority” of people who had shared their opinions on the impending security law had given positive feedback.

“The general opinion gives me the impression that [the public] are in support of the overall goal of enacting Article 23 to ensure that we protect ourselves when people want to cause damage to us,” he said in Cantonese.

Hong Kong has plummeted in international press freedom indices since the onset of the security law. Watchdogs cite the arrest of journalists, raids on newsrooms and the closure of around 10 media outlets including Apple Daily, Stand News and Citizen News. Over 1,000 journalists have lost their jobs, whilst many emigrated. Meanwhile, the city's government-funded broadcaster RTHK has adopted new editorial guidelines, purged its archives and axed news and satirical shows.

See also: Explainer: Hong Kong’s press freedom under the national security law

In 2022, Lee said press freedom was "in the pocket" of Hongkongers but "nobody is above the law." He has also repeatedly told the press to "tell a good Hong Kong story."

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

LATEST FROM HKFP

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.