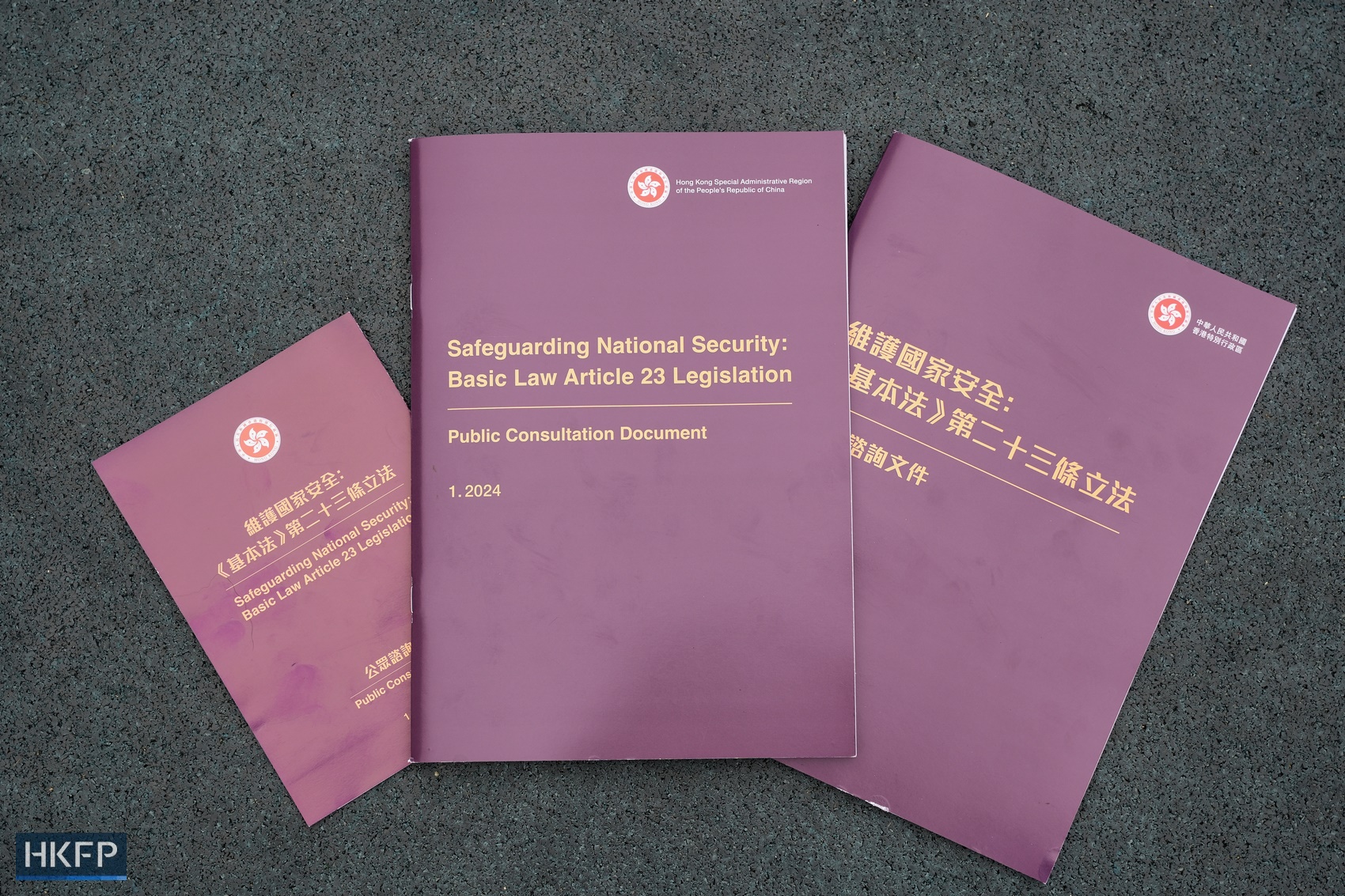

Chief Executive John Lee has announced the start of the government’s second attempt to introduce local legislation on national security as required by the Basic Law’s Article 23. The first attempt in 2003 ended in failure amid widespread public protest. This time Hong Kong’s patriots-only political elite cheered.

Legislators and business leaders immediately and unanimously endorsed the proposals, which are more comprehensive and draconian than those offered in 2003. The external environment is also different. Mainland Chinese leaders are now laser-like focused on security and geopolitics is more contentious.

The government’s Article 23 national security proposals are embedded in mainland China’s expansive concept of security, that identifies at least 20 different types. The proposals expand the scope of existing law; clarify offences; introduce new offences (insurrection, external interference, etc.) and substantially strengthen the power of the police to regulate civil society via an amended Societies Ordinance.

Authorities identify five types of national security crime that are sometimes overly broad and err on the side of security in a trade-off with human rights. Because the proposals are embedded in the central authorities’ all-encompassing notion of national security, we should take note of mainland China’s national security policy and practice as we consider the government’s proposals. One proposed offence, the theft of state secrets, brings the issues into sharp relief.

First, the mainland Chinese definition of state secrets – words not found in Hong Kong’s current Official Secrets Ordinance – is both broader and narrower than the definition proposed for Article 23.

Article 2 of the 2023 mainland Chinese draft law on safeguarding state secrets says: “State secrets are matters relating to the security and interests of the state, determined in accordance with legal procedures, and restricted to a certain range of persons for a certain period of time.” This wording appears to equate state secrets with national security.

In Hong Kong, however, authorities propose that “protected information” as used in the Official Secrets Ordinance becomes a “state secret” only if “disclosing it without lawful authority would likely endanger national security.” Still, the protected information, or secrets, that could become “state secrets” under this condition includes seven very broad categories, mostly following the central authorities’ lead.

These are: 1) “major policy decisions” on the affairs of China or Hong Kong; 2) defence and the armed forces; 3) diplomacy and external affairs; 4) “economic and social development” of China or Hong Kong; 5) “technological development or scientific technology” of China or Hong Kong; 6) “secrets concerning activities for safeguarding national security or the security of the HKSAR, or for the investigation of offences.”

Local authorities did not copy the mainland’s seventh type of secret: “other secret matters determined by the administrative departments of state secrecy,” which seems to open the floodgates to almost anything.

Nor did our officials include the additional provision that “the secret matters of a political party that meet the requirements of the preceding paragraph [reference Article 2 of the mainland law] are state secrets.”

Rather, in the Article 23 proposal officials state that a seventh type of secret is “the relationship between the central authorities and the HKSAR.” The “central authorities” is a euphemism for the Chinese Communist Party and the central people’s government.

Strangely, officials offer no justification for the inclusion, in a document replete with justifications, many of which reference the 2019 “social chaos” or overseas laws. In this, the government appears to have copied the language of the 2002 Article 23 proposals. Rather, the 2002 proposals argue that continuing to classify relations between central authorities and Hong Kong as “international relations” would no longer be appropriate after 1997. True.

Then, without offering any justification, authorities proposed a “new class of protected information:” relations between the central authorities and Hong Kong “to protect such information from unauthorised disclosure.”

Given the broad scope of secrets, why is this provision necessary? The mainland Chinese law on state secrets does not contain such central-local provisions. Is Hong Kong’s proposal a fig leaf to cover the special position of the Chinese Communist Party as the ruling party in Hong Kong? Given the all-inclusive nature of secrets, as above, is this necessary?

The mainland law is also more narrowly drawn in that state secrets are time-bound, “restricted… for a certain period of time.” The provision implies that secrets be archived and managed with an expiry date. Hong Kong still does not have an archives law requiring that all public bodies maintain archives and laying down their management, including rules on the expiration of confidentiality, allowing secrets to eventually be made public.

Accountability demands such a law and such practices for our state secrets. Not to include this kind of provision allows officials to escape responsibility for their actions, a practice not in keeping with good governance.

Second, although authorities promise to balance appropriately security and human rights, their proposals often err on the side of security. Consider the crime of disclosing state secrets. Mainland Chinese experience is instructive. By 2003 officials across the border had classified the outbreak of epidemics as state secrets, ruling that disclosing information about epidemics would damage national security.

Then came SARS. Only after a whistleblower disclosed to the media SARS-related state secrets did authorities alert the public to the danger. Undoubtedly the whistleblower, a PLA general and medical doctor, had no intention of damaging national security. Rather, he sought to alert the public to an imminent danger. As the Article 23 proposals state, intentions matter. Mainland Chinese authorities subsequently recognised and offered formal protection to whistleblowers.

The Hong Kong government does not recognise whistleblowing, nor does it entertain the very real possibility that a public servant may see “negligence or abuse that is of great public interest” and “may be an imminent threat to the public.” Rather, local authorities counsel civil servants to report to the police, ICAC, or their superiors if they see illegal behavior, negligence, maladministration and the like.

By offering a public interest exception in Hong Kong, authorities could recognise and try to protect legitimate whistleblowing. As other mainland cases show, however, official protection may not always be effective. Witness the treatment of Covid-19 whistleblowers in Wuhan in 2020. Protection does, however, officially acknowledge that whistleblowing can sometimes save lives and improve governance.

The emphasis on secrecy and security in the Article 23 proposals is likely to strengthen the tendency of authorities, who are mostly risk-averse, to over-classify information. This opens the way for further national security creep. As we have seen in mainland China, overclassification can have devastating consequences.

The Article 23 proposals require the public to trust the authorities that the government will appropriately balance security and human rights. Officials seek to reassure us that they will allow opinion – “reasonable and genuine criticism of government policies based on objective facts” – and analysis that points out issues with government policy and practices if they are aimed at improving Hong Kong’s governance.

Referring to state secrets, officials state that measures should seek to protect “only those types of information which must be kept confidential to safeguard national security and the means of protection should be clearly prescribed so as to strike a proper balance between the protection of state secrets and the protection of the right to freedom of speech and expression.” These principles are welcome. How officials will implement them, in our low-trust environment, we have yet to see.

Experience teaches that much more important than the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance, whatever its content – we still do not have proposed penalties – are the rules implementing the national security regime.

The Article 23 proposals outline a national security regime providing officials with substantial discretion. The implementing rules constrain discretion to some extent. That is, the rules for implementing the official secrecy regime are more important than the general provisions of Article 23, especially if they are made within a culture of secrecy that tends to pervade government. Will these be publicly discussed and debated?

Hong Kong’s Article 23 proposals should be accompanied by recognition and protection of whistleblowers in law, an archives law making it a legal requirement that public bodies keep archives and centralise and standardise their management, and a transparency of information law to regulate the declassification of secrets including state secrets – all of which, borrowing from the mainland, should be time-restricted. This is the bare minimum for accountable government.

In 2018 authorities reassured us that the government sought to be, “as far as possible, open and transparent and accountable to the public.” We would all welcome officials restating and practising this pledge.

Type of Story: Opinion

Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the interpretation of facts and data.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.