By Su Xinqi

Cardinal Joseph Zen fled the communist takeover of China as a teenager and found sanctuary in Hong Kong, a bastion of religious freedom that he now fears could disappear under Beijing’s tightening grip.

The 88-year-old former bishop of Hong Kong has spent his retirement looking on with increasing alarm at the Vatican’s embrace of Beijing – and the recent imposition of a sweeping security law on the finance hub has only heightened his fears.

“As I can see in the whole world, where you take away the freedoms of the people, religious freedoms also disappear,” Zen told AFP from the Salesian Mission he joined as a novice seven decades ago.

Hong Kong has been a haven for faiths both before and after its 1997 handover to China.

On the authoritarian – and officially atheist – mainland, religion is strictly controlled by the Communist Party. Under President Xi Jinping crackdowns have intensified, from the demolition of underground churches to the widespread incarceration of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang and a new campaign to “Sinicise” religions.

In contrast, Hong Kong boasts a dizzying array of faiths, including proselytising groups barred from the mainland such as the Latter Day Saints, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Falun Gong.

But Zen wonders how long that can last.

VIDEO: Hong Kong's Cardinal Zen, 88, has spent his retirement looking on with increasing alarm at the Vatican's embrace of Beijing — and the recent imposition of a sweeping security law on the city has only heightened his fears pic.twitter.com/v5Hd2EKCX4

— AFP news agency (@AFP) October 8, 2020

After huge and often violent democracy protests convulsed Hong Kong last year, China’s leaders launched a clampdown on its opponents in the semi-autonomous city.

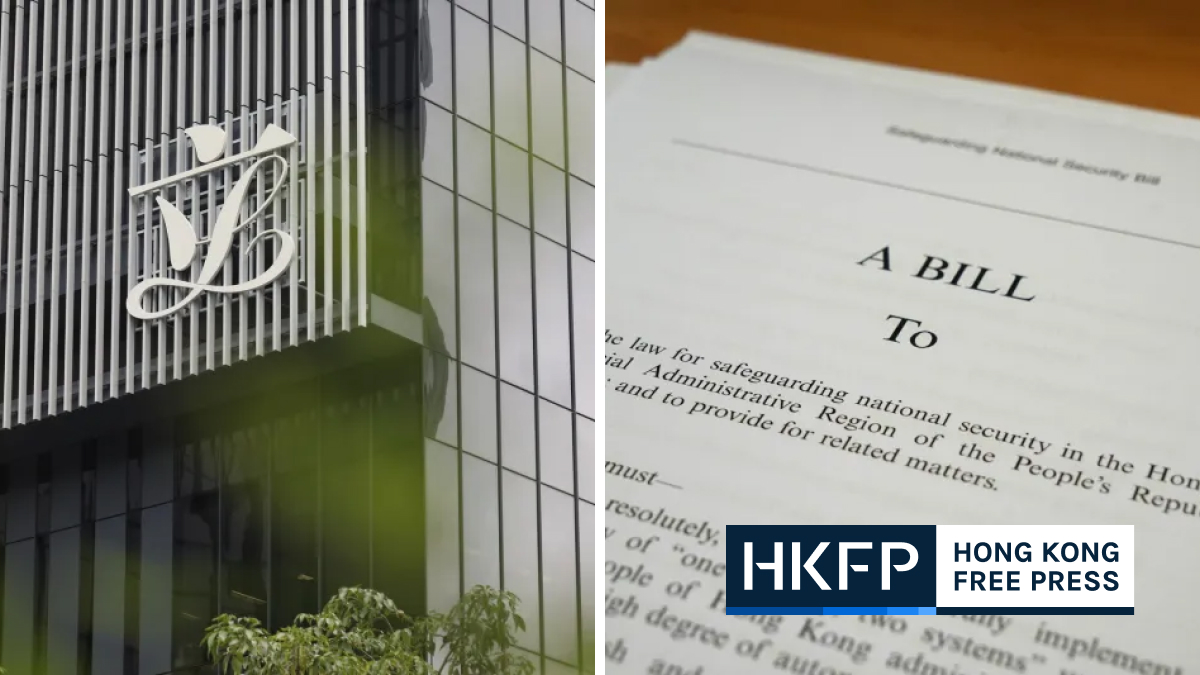

In late June, they also imposed a broadly worded security law that outlawed certain views and ushered in a new political chill.

A divided flock

Authorities say religious freedom will not be affected by the sweeping new law, which targets secession, subversion, terrorism and colluding with foreign forces.

But Zen believes the writing is on the wall.

“I think the law requires absolute obedience to the government,” he said.

Hong Kong’s religious communities reflect the city’s own political divisions and diversity.

Many churches have Beijing loyalist congregations and city leader Carrie Lam is herself a devout Catholic. The head of Hong Kong’s Anglican Church is a member of a top political advisory body in Beijing.

Shortly before the new security law was unveiled, Beijing’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong gathered more than 50 religious leaders.

It said it obtained more than 20 blessings for the law – including from acting Catholic leader Cardinal John Tong as well as a number of prominent pro-government Protestant and Evangelical churches.

Tong has been especially vocal. In two recent letters, he criticised clergy for “inciting hatred” by discussing politics in sermons and warned that people sympathetic to the democracy protests were undermining social harmony.

“He thinks that this law would have nothing to do with religious freedom. He is very optimistic,” remarked Zen.

But he conceded that Tong is “in a difficult position” with the Vatican and Beijing preparing to renew a historic deal on the appointment of bishops in China, where Catholics are split between a government-run association and an underground church loyal to Rome.

“When you are asked to take position, what can you say,” he said.

Pastors flee

Not all religious leaders are comforted by assurances their freedom will remain intact.

Many churches in Hong Kong view China’s Communist Party with deep suspicion and openly support the democracy movement.

Some leading figures of earlier protests in 2014 were evangelicals such as Benny Tai, Chan Kin-man and Reverend Chu, all of whom were eventually convicted for their activism.

Then, when last year’s much larger democracy protests exploded, sympathetic churches often opened their doors to crowds fleeing tear gas, and the hymn “Sing Hallelujah to the Lord” became a protest anthem.

When Beijing appointed Xia Baolong to head its Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office in February, much local media attention focused on how the Xi loyalist oversaw a campaign demolishing church crosses in China’s Zhejiang province.

With police ramping up arrests against protest leaders, some religious figures have joined those leaving Hong Kong for good.

In August, Wong Siu-yung and Yeung Kin-keung, two evangelical pastors who signed a joint “Gospel Declaration” critical of Beijing, announced they had fled overseas to an undisclosed destination.

The May declaration called on followers to “reject all lies and bravely point out the wrongs done by the state” and to resist any “totalitarian regime”.

Two months later, pro-Beijing newspapers in Hong Kong accused the pair of “inciting secession and subversion” – two of the new national security crimes.

Veteran pro-democracy pastor Yuen Tin-yau said he believed it was naive to think the security law would not affect the faithful.

“It’s a wide strike on freedoms and human rights,” he told AFP. “Religious freedom cannot stand aloof and unscathed.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team