Media outlets should be “cautious” and consider whether elements of “abetting” are involved when interviewing wanted Hong Kong activists, the justice minister has said.

Interviews with overseas Hongkongers who are wanted by the authorities may amount to giving them a platform to express views in breach of national security, Secretary for Justice Paul Lam warned last Friday in an interview with NowTV.

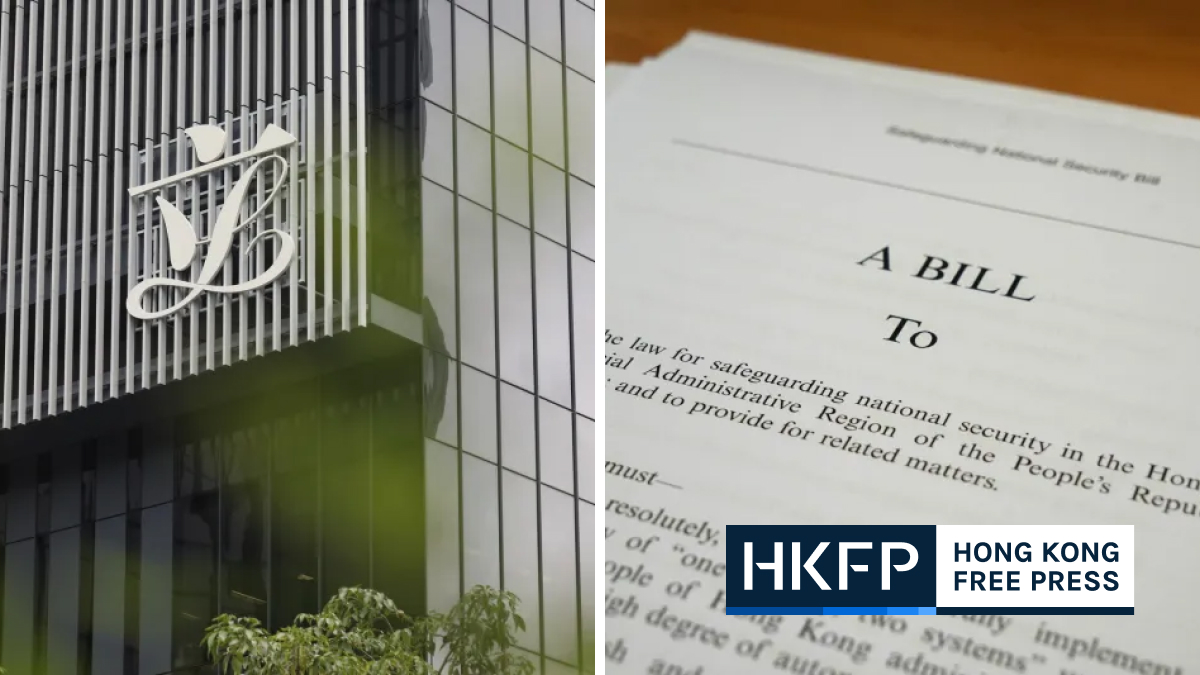

Lam’s remarks came a few days after the government initiated a four-week consultation exercise for the enactment of the city’s domestic national security legislation as required under Article 23 of the Basic Law.

Article 23 of the Basic Law stipulates that the government shall enact laws on its own to prohibit acts of treason, secession, sedition and subversion against Beijing. Its legislation failed in 2003 following mass protests and it remained taboo until after the onset of the separate, Beijing-imposed security law in 2020. Pro-democracy advocates fear it could have a negative effect on civil liberties but the authorities say there is a constitutional duty to ratify it.

See also: Article 23 then and now: What changed between 2002 and 2024

“[Y]ou go to interview them, giving them a platform, allowing them to have that platform, essentially conveying the same message – could there be an element of abetting? I believe one should be cautious about this matter, and I don’t think it’s something done unintentionally,” he said in Cantonese.

Speaking on the same television programme, Secretary for Security Chris Tang said that whether the media would risk breaking the law by interviewing wanted activists would depend on “different circumstances.”

“Interviewing someone is simply conducting an interview. However, if there is an appeal for others to donate money to them after the interview, could that be considered as assisting these fugitives? It depends on the specific context and circumstances,” he said in Cantonese.

Last year, the Hong Kong government placed a HK$1 million bounty each on 13 activists who left the city, including ex-lawmakers Ted Hui and Dennis Kwok, activists Nathan Law, Simon Cheng and Joey Siu and solicitor Kevin Yam.

They were accused of inciting secession and subversion and colluding with foreign forces by calling for sanctions against Hong Kong and Chinese officials, meeting foreign politicians and giving interview.

Press freedom is meant to be guaranteed under the city’s mini-constitution, as well as the security law, with no explicit clauses about who journalists may-or-may-not speak to. Among the 17 allegedly “seditious” articles being considered in the case against local outlet Stand News are interviews with, and commentaries by, self-exiled democracy activists Baggio Leung, Sunny Cheung, and Nathan Law.

Public interest defence

Interviews with activists are not the only concern when it comes to the looming local security law. Last week, the Hong Kong Bar Association Chairman Victor Dawes said the suggestion of adding a public interest defence against the proposed offence of disclosing state secrets under the Article 23 legislation was “certainly worth considering.”

But, if such a defence were to be included, the threshold must be stated clearly and could not be “too low,” the senior counsel said.

The authorities suggested defining state secrets along Beijing’s legislative line, covering information relating to major policy decisions, as well as China’s socioeconomic and technological development.

Lam told NowTV last Friday that there could be “extreme circumstances” in which the public interest would come before the protection of state secrets, such as when people’s lives were at stake.

”Public interest could outweigh the need to maintain the confidentiality of state secrets. However, even in such exceptional circumstances, the threshold for disclosure must be very high,” he said.

In June 2020, Beijing inserted national security legislation directly into Hong Kong’s mini-constitution following a year of pro-democracy protests and unrest. It criminalised subversion, secession, collusion with foreign forces and terrorist acts, but it did not target all seven offences listed in Article 23.

Chief Executive John Lee said last June that the homegrown security law would “definitely” be enacted within that year or the next year at the latest, before vowing during last year’s Policy Address that legislation would be completed in 2024.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team